Researching Virginia WWI Ancestors

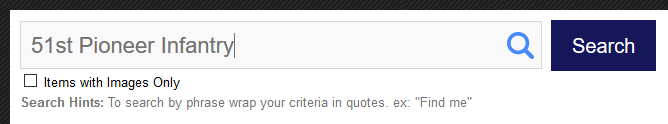

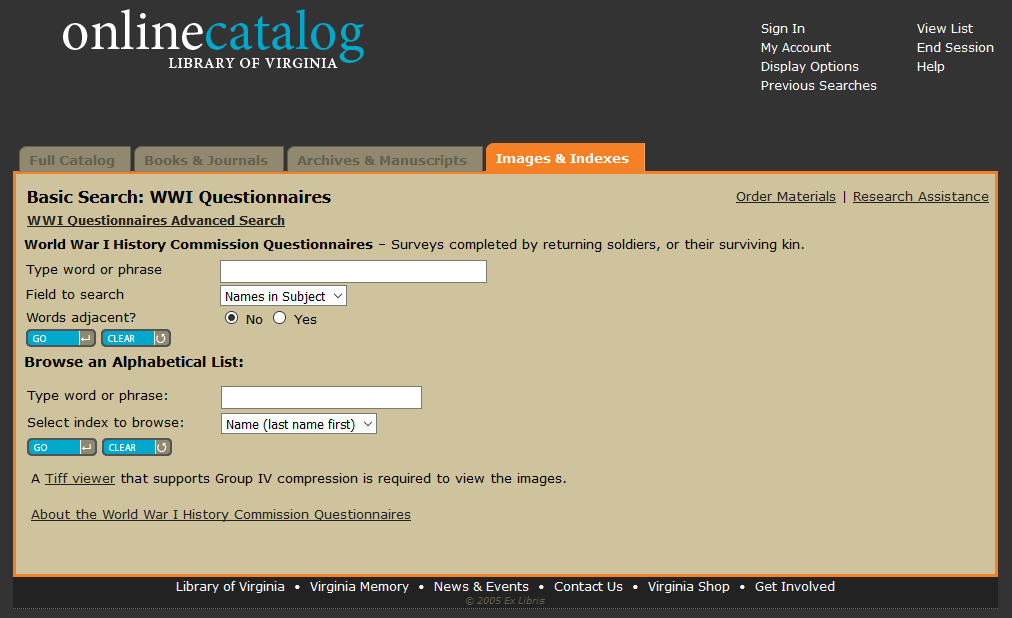

As you may know from my lectures and book, it is important to find your WWI ancestor’s military organization. An online way to find out about your Virginia WWI Ancestors is to check the WWI questionnaires posted at the Library of Virginia.

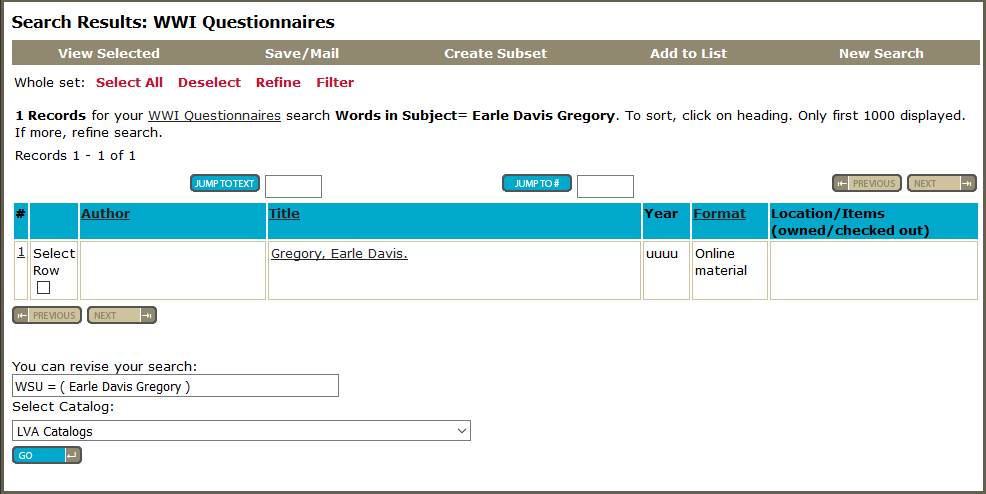

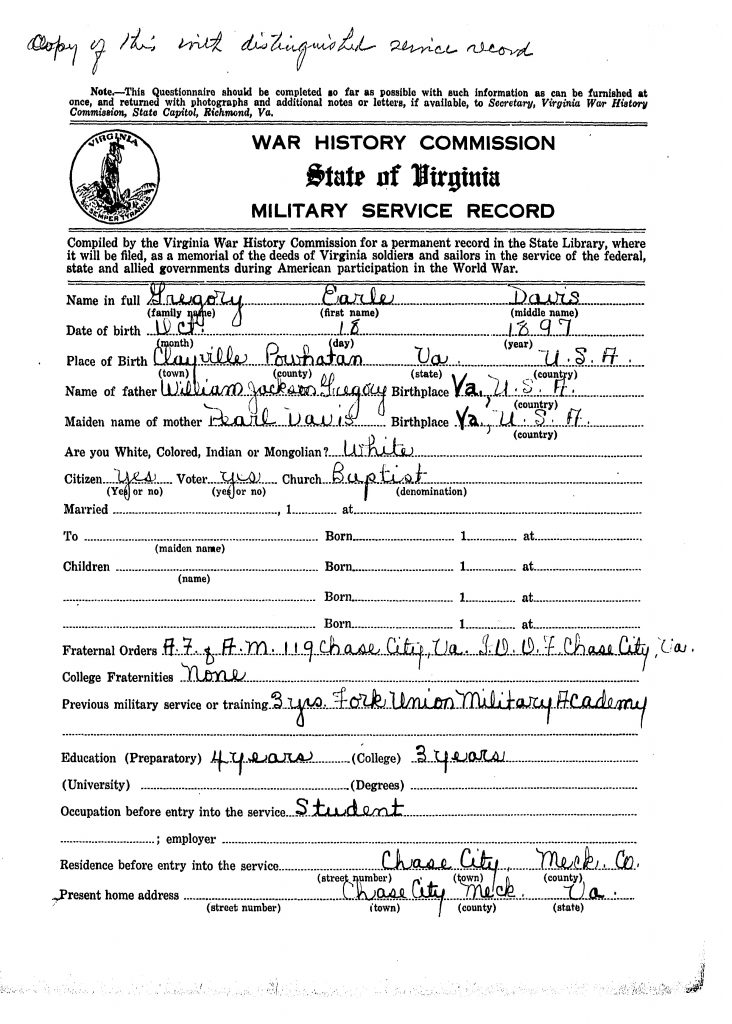

For this example, I searched for a record for SGT Earle Davis Gregory. He was the only Medal of Honor winner in WWI from Virginia.

Click on the name to find out more about the record.

A window pops up with links to look at or download the survey pages

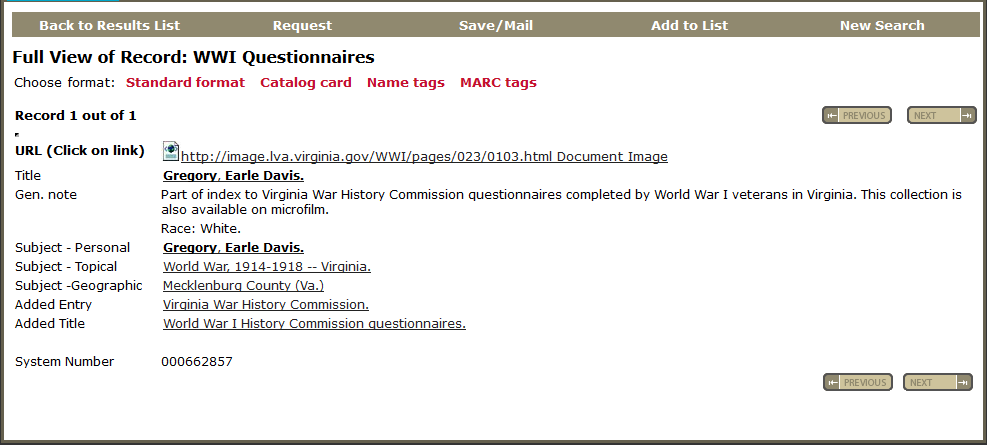

This record is his personal survey.

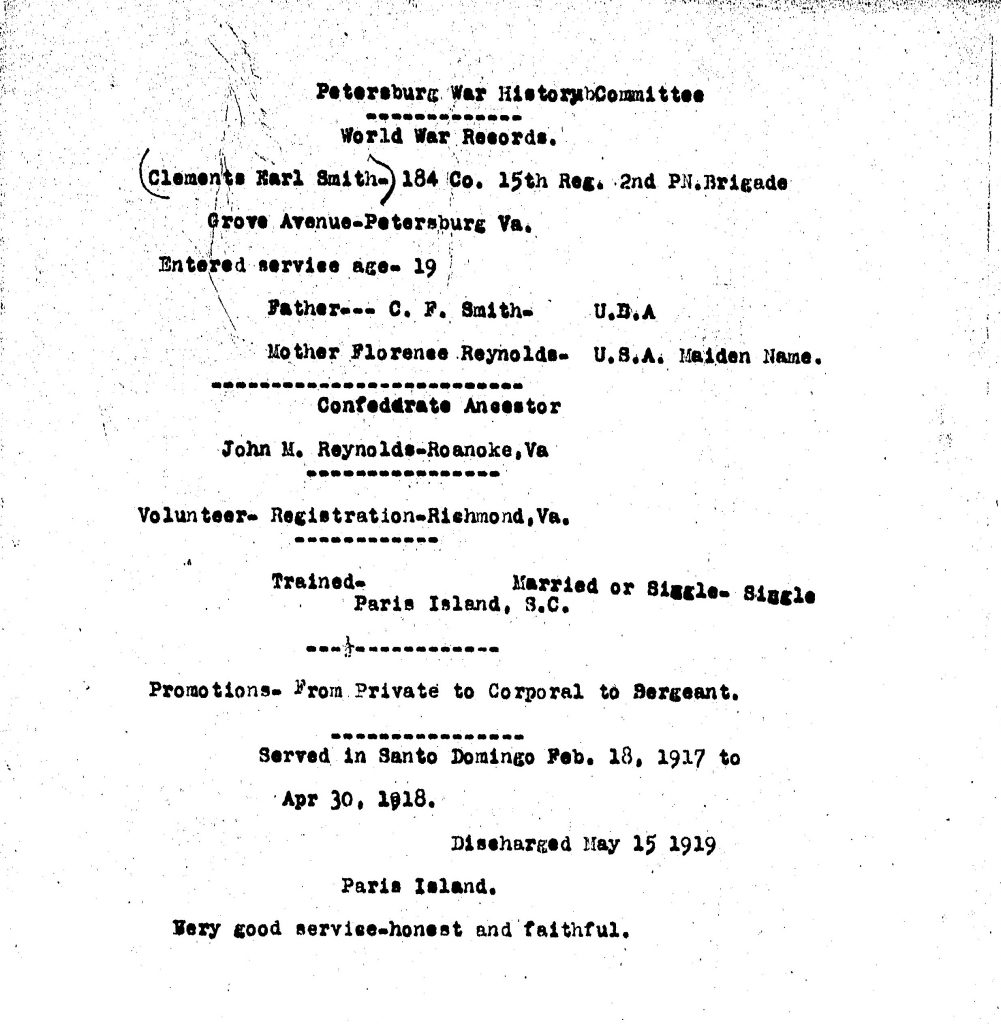

While searching, I found this record with information about the soldier’s service, an ancestor, and his mother’s maiden name.

Virginia’s WWI and WWII Centennial Commission has resources that may help you learn more about Virginia in the World Wars. On this website you can find WWI Profiles of Honor Stories.

Be sure to check out the resources on the WWI Centennial Commission Website for Virginia.