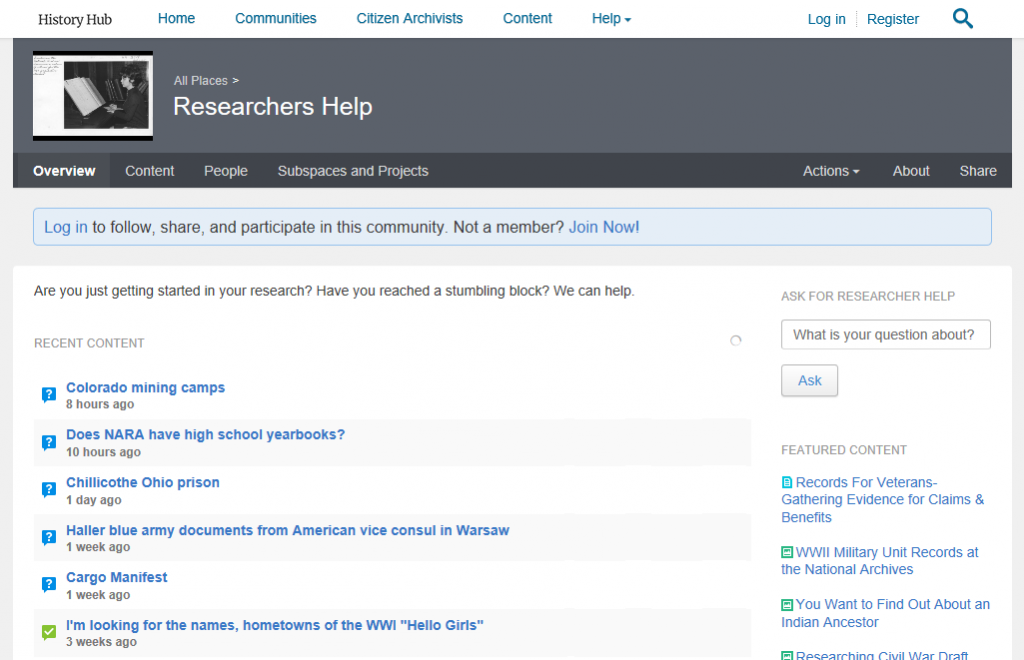

7 Ways to Research WWI Veterans in Your Community

Seventy First Regiment Leaves for Camp of N.Y. Division.(NARA RG165-WW-288C-067)

Congratulations on taking the first step of wanting to learn more!

Ryan Hegg of the WWI Centennial Commission for New York City asked me if I believed that the WWI Generation was really the Greatest Generation. What a thought provoking question! Ryan makes a great case. WWI was a defining point in our Country’s history as a participant on the world stage. Theirs was a generation who decided to go overseas to fight the Great War for Civilization. They experienced the Great Depression.

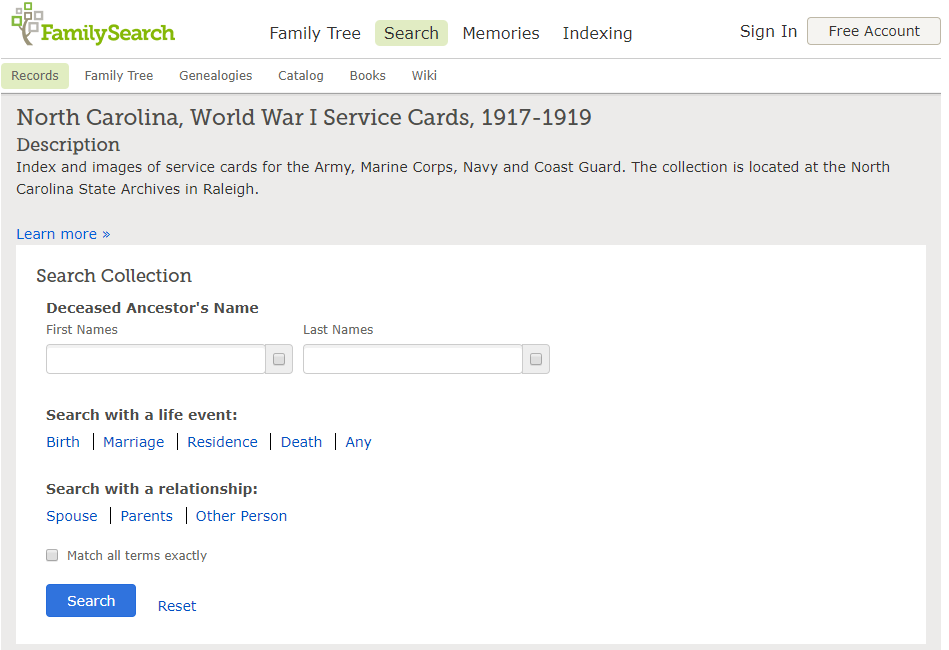

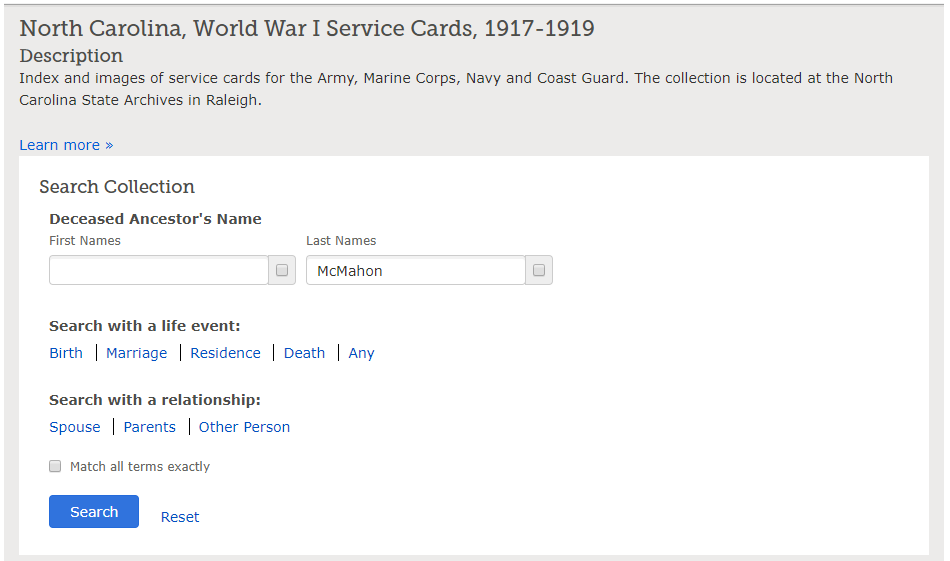

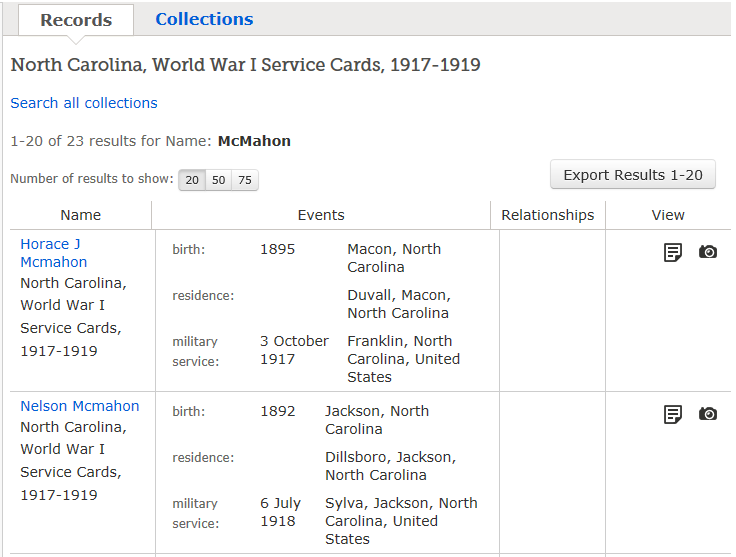

Students have a number of resources to find WWI veterans who were residents in their communities. The ideas below start with those that take least effort to those that require more advanced skills. (For those who do not know if they had ancestors who served in WWI, a future blog post will cover that topic.)

- Locate a WWI Memorial in your city or town. There may be a statue in a park or a plaque in a public building. You can contact your city or town office to ask if such a memorial exists. When you locate the memorial, you can take pictures of it and copy the names that you find. If you want to learn more about those individuals try some of the other steps.

- Ask at a local cemetery about WWI veterans’ graves. The tombstones for service members who died during the war or later should show the branch of the military, the war, and their military organization. The cemetery office should be able to help you locate the graves of WWI veterans.

- Go to your local library and ask to speak to the research librarian. The library may hold special books telling about local men and women who served in WWI. There many also be files of materials donated by local researchers, which may be called vertical files. They may have fold local newspapers or files of newspaper clippings.

- Contact the local chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). Each Post is unique and has different polices pertaining to its community service efforts. You can visit VFW’s Find-A-Post feature here to locate a VFW Post and its contact information. Ask to speak with the Commander or Quartermaster.

- If there is a local historical society, genealogical society, or historical museum in your area, call or send an email. I have found WWI collections in unlikely locations, such as the Laws Railroad Museum and the Holland Land Office Museum.

- Research local newspapers of the time. You can check the Library of Congress Chronicling America website to find out what newspapers existed at the time, and see if any of them have been digitized. Many community newspapers printed articles about the men and women who served. Search for WWI and your community name.

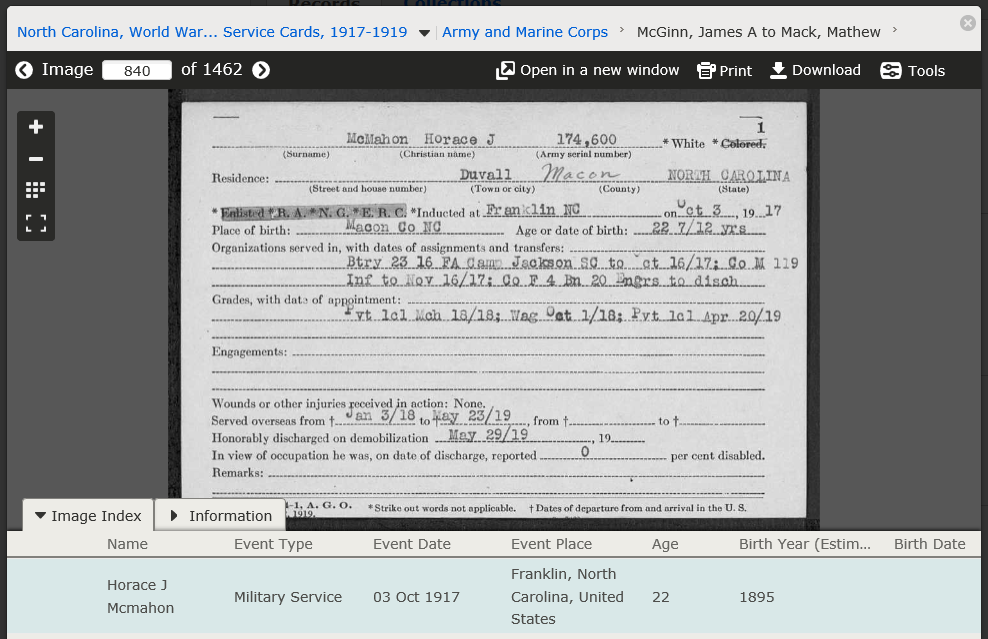

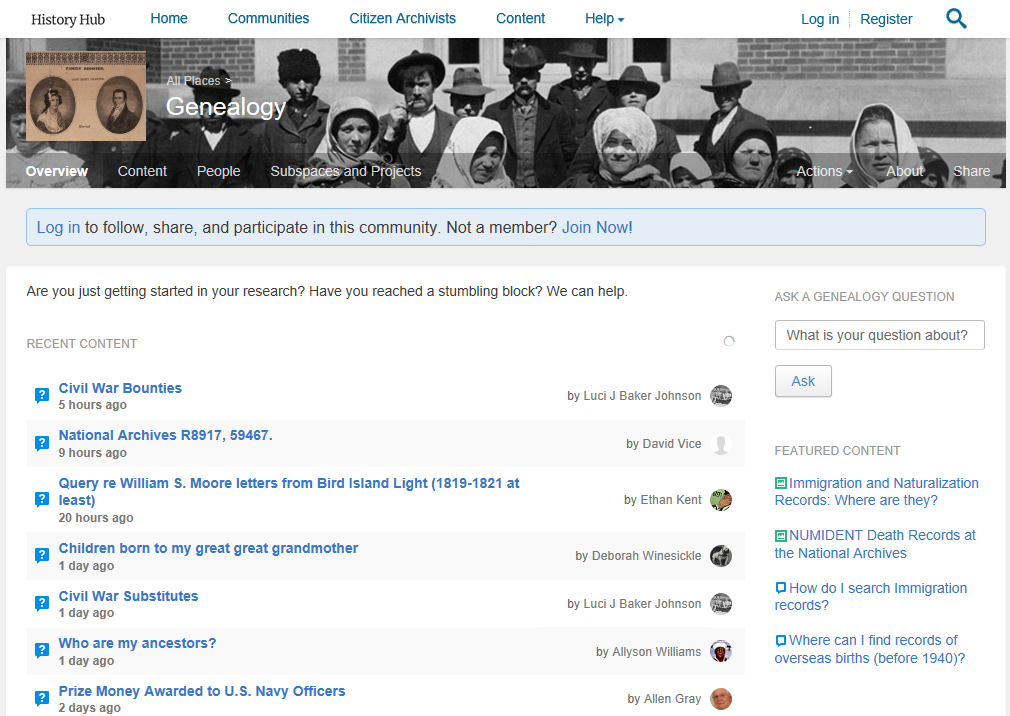

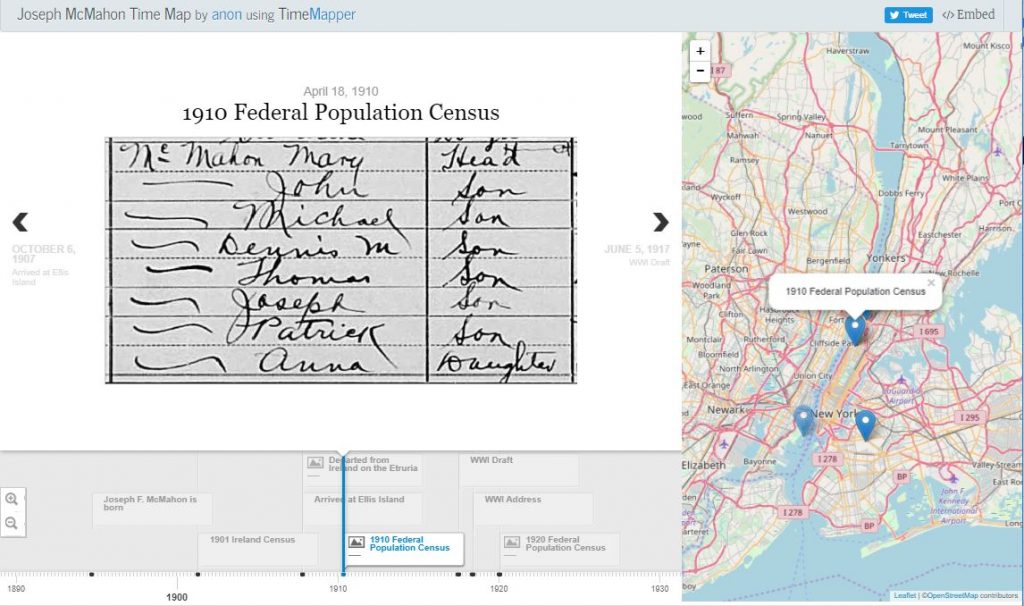

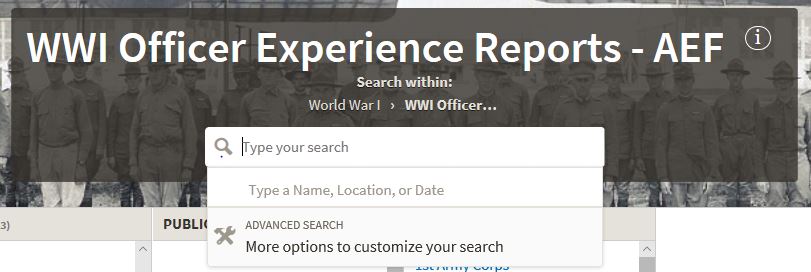

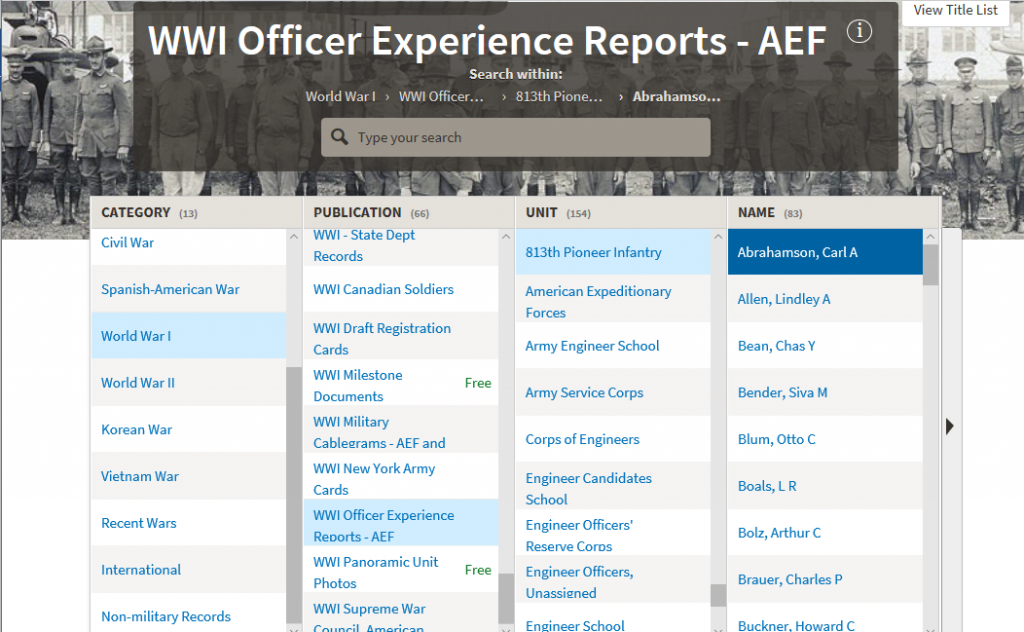

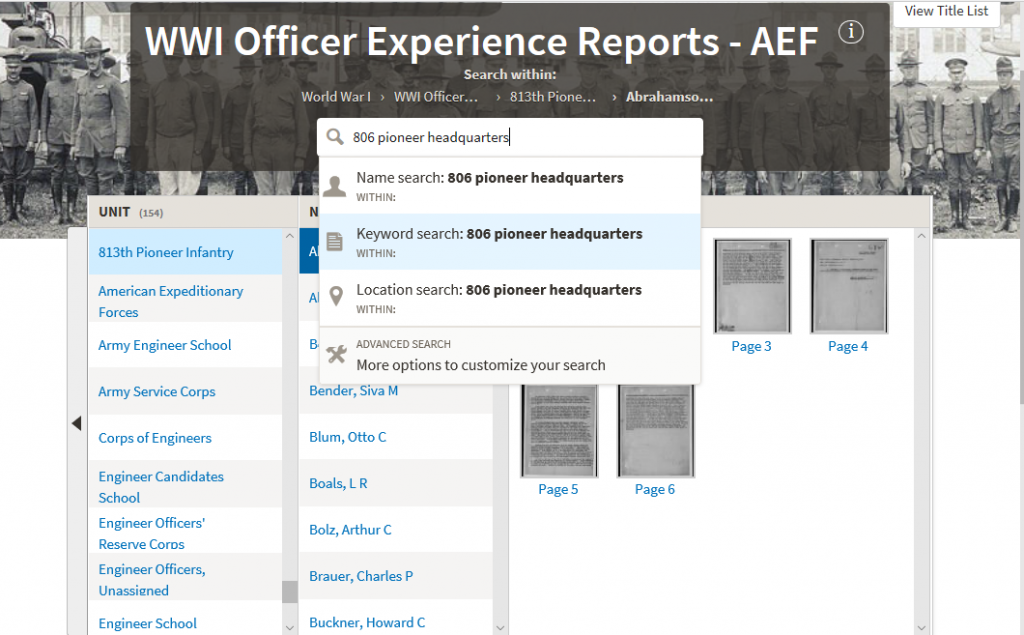

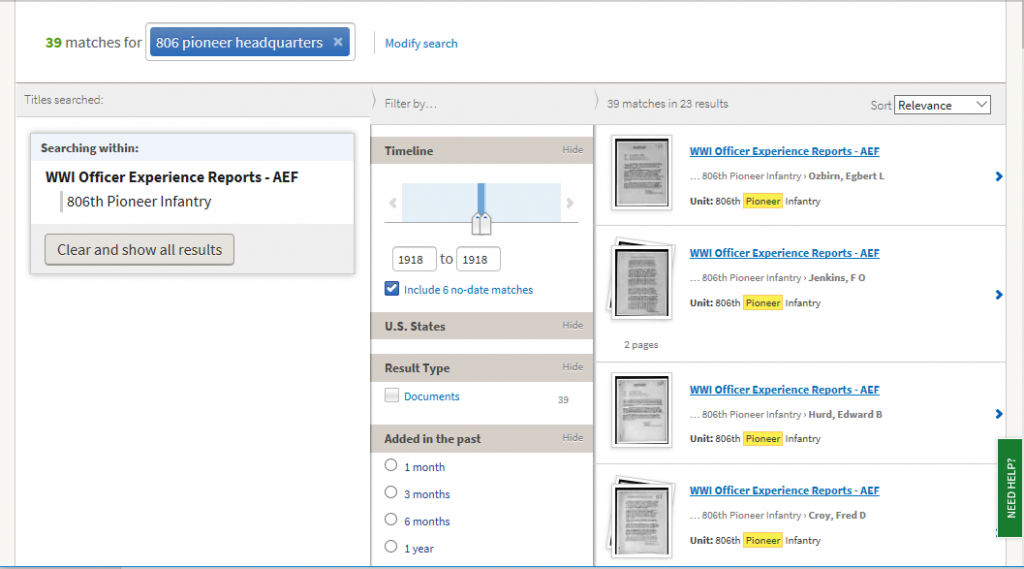

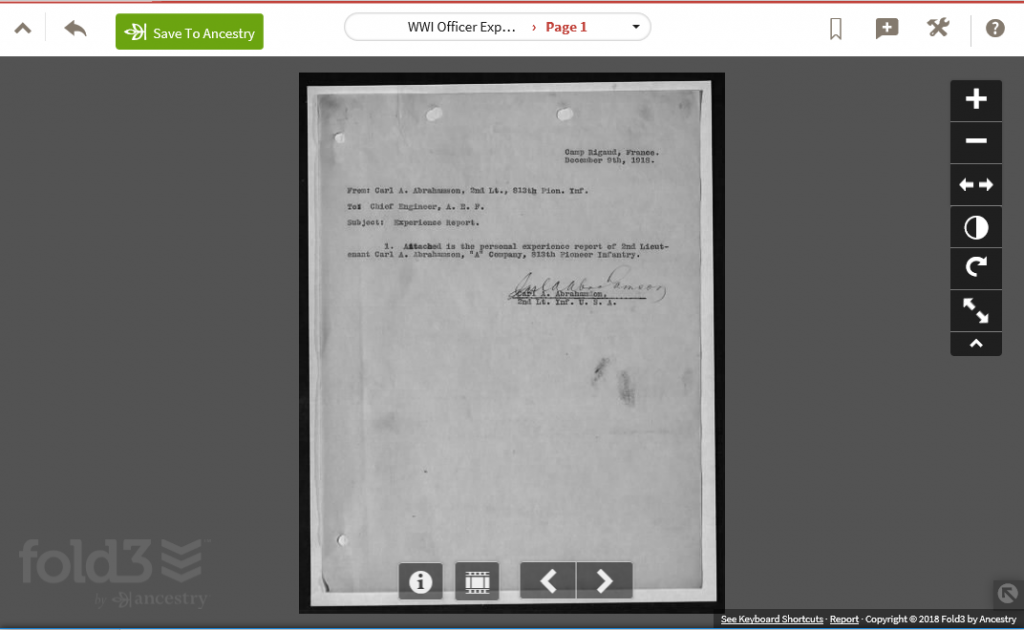

- Head back to your library and find out what databases are available. Your local library may have access to Ancestry.com, Fold3.com and ProQuest and other Historical Newspapers. Librarians should be able to help you search for more about a specific WWI Veteran using his or her name.

Beyond these steps, much of the research involves looking for material about a military organization in which the veteran served. There are several posts on this blog about learning more about WWI Veterans.

Good luck!