Researching Soldiers who died during World War I

By all means, search the ABMC Burials and Memorials to see if the soldier rests in Europe. But, you may not find his name is in the database, and there may be more to the story.

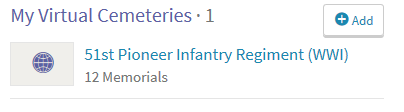

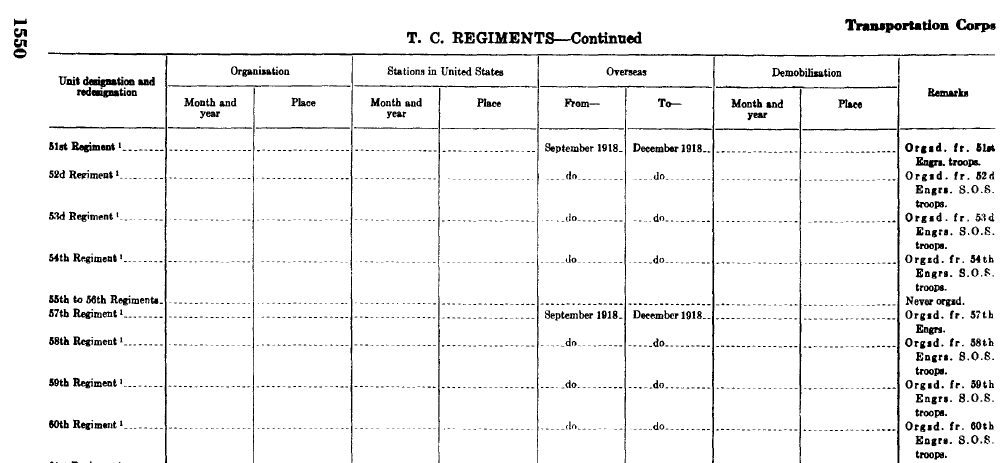

Individual Combat units were responsible for burying the deceased soldiers and marking the grave. Then the Graves Registration Unit was responsible for moving the deceased to U.S. cemetery graves. The 51st Pioneer Infantry History tells of GRU work.

But, even if the deceased soldier was buried overseas, his remains may have been returned to the U.S. in 1920 or 1921. The decision whether to leave a soldier at an overseas cemetery or bring him home was made by the next of kin. In October of 1919, the War Department contacted the next-of-kin of every deceased soldiers, and each was given the option to bury them in American military cemeteries in Europe, or have them shipped home for burial in a military or private cemetery. 46,000 of the soldiers’ remains were returned to the United States. It took over $30 million and two years to return the remains of 46,000 soldiers. 30,000 soldiers were buried in the cemeteries in Europe. The government also paid the travel expenses pilgrimages for Gold Star mothers, and widows, to visit these graves.

The Burial Files and Graves Registration records are part of the Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General (Record Group 92). You can find the Individual Burial Files at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, MO. These are also called the “Cemeterial Files” or “293 Files” and contain: Correspondence, Reports, Telegrams, Applications, and Other Papers Relating to Burials of Service Personnel. Check out The Sick and the Dead, Veterans Administration Claim Files and World War I Burial Files by Archivist Daria Labinsky.

There were many similarities between the Americans and the Australian soldiers, who fought so far from their homeland. Australia would not pay for mothers to visit the graves of their sons, as it was a dangerous and expensive proposition.

Let’s see what we can do to locate the final resting place of these fallen soldiers:

Search the American Battle Monuments Commision (ABMC) for an overseas grave.

If the soldier is not in the ABMC database, then it is worth searching in the United States for the soldier’s grave.

Searching the U.S. Army Transport Service records on Ancestry.com would confirm that the soldier’s body was returned to the U.S. These records contain the soldier’s serial number and the soldier’s military organization. If you do not have a subscription to Ancestry.com, remember that you may be able to access Ancestry.com in may be available in your local library, or at a nearby Family History Center.

Even if you do not have access to Ancestry.com, you can still try to locate the grave.

First, search in National Gravesite Locator to see if the soldier was buried in a military cemetery.

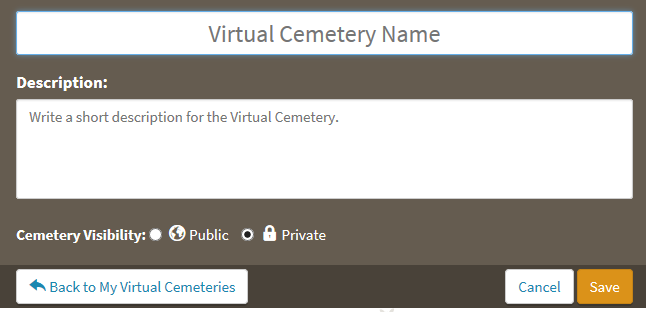

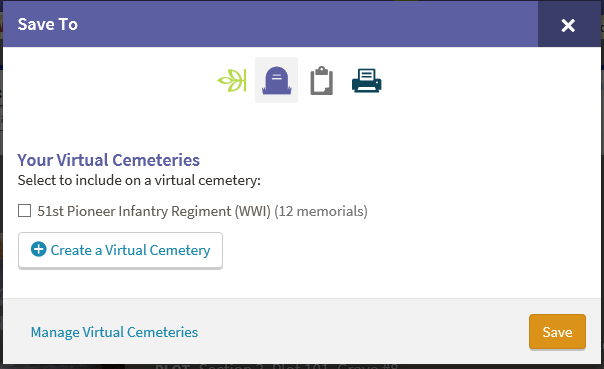

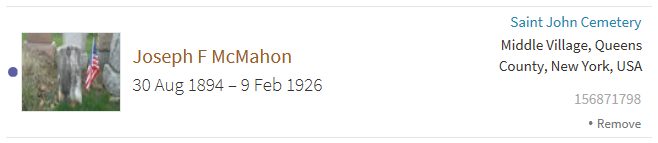

If the soldier cannot be found in a military cemetery, try Findagrave.

Many of the fallen soldiers are documented in the three volumes of the Soldiers of the Great War:

Vol 3 Oklahoma – Wyoming Volume 3 also contains an index by volume, by state and by first letter of the last name. The index to Vol 1 Begins on page 499, and the index to Vol 2 Begins on page 501.

The photos in the book are not in alphabetic order, and not every soldier has a picture.