Researching Tennessee WWI Ancestors

More than 130,000 Tennesseans served in WWI. If you are researching one of them, then check out the extensive collection of online WWI resources from the Tennessee State Archives. This archive contains items ranging from the compiled service records that are such an important starting place for WWI research, to a very special and personal collection of digitized items shared by descendants. They are hosted by the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC), which is a global library cooperative.

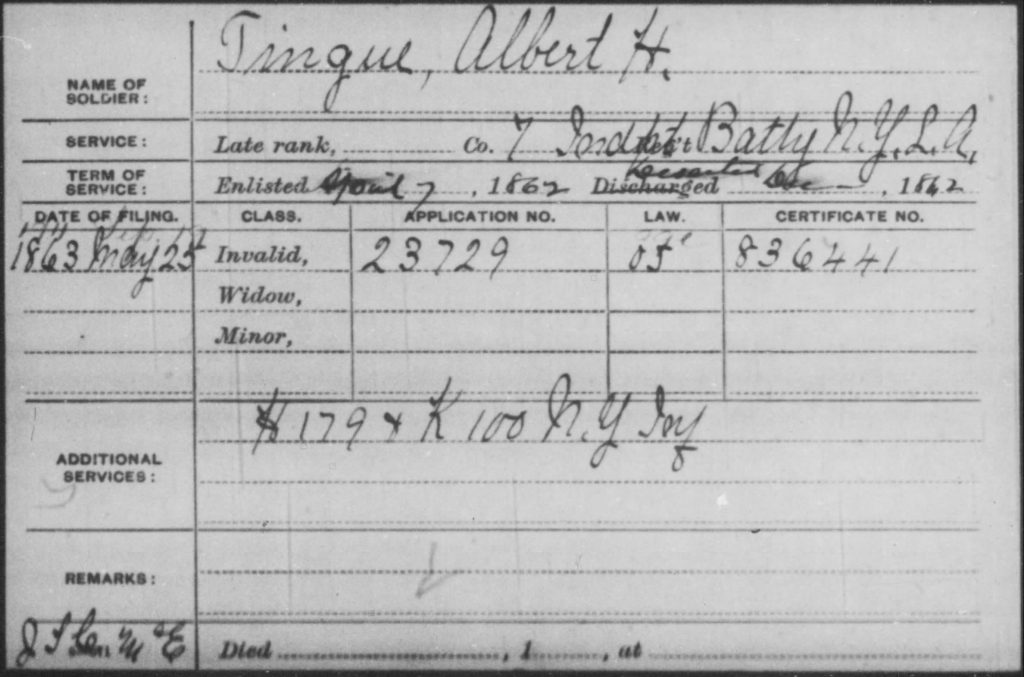

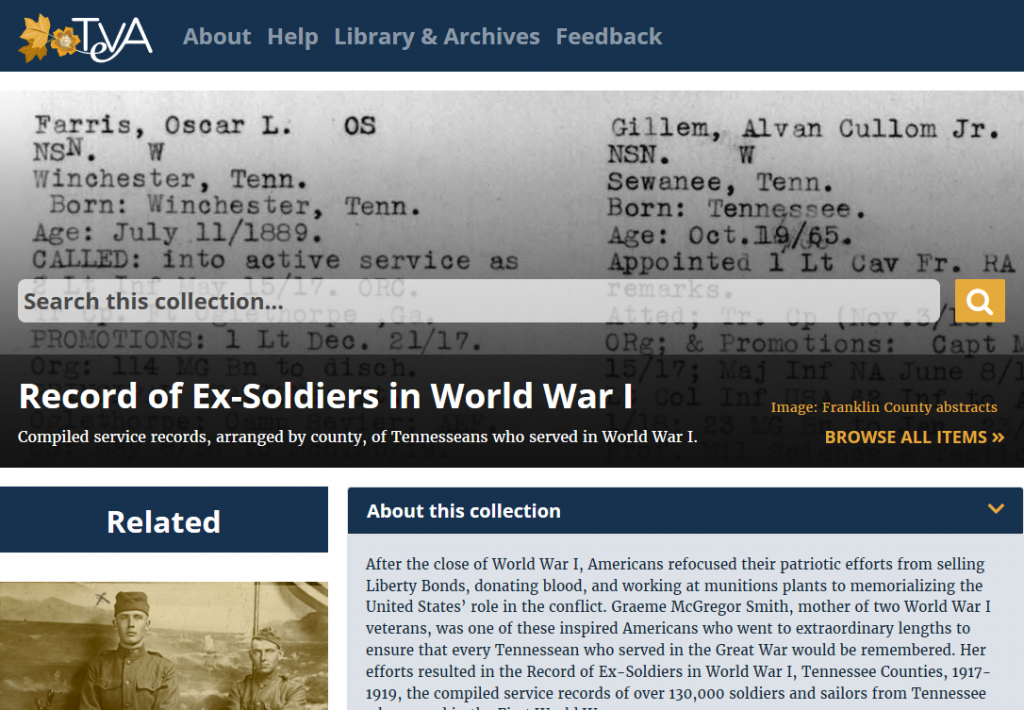

The compiled service records of the WWI soldiers and sailors from Tennessee can be found in the Record of Ex-Soldiers in World War I. You can search for a specific service member from this webpage. Since the records are stored by county, you also have the option to browse them.

On this webpage you will also find links to Gold Star records from Tennessee, the “Over Here, Over There” collection and Alvin York’s record. The Gold Star records should definitely be checked if you are researching someone a Tennessean who died in service. To check the comprehensive list of all Tennesseans who died in WWI, you can email TLSA and they will perform a lookup in the complete listing of the dead in the Court of Honor in the War Memorial Building in Nashville.

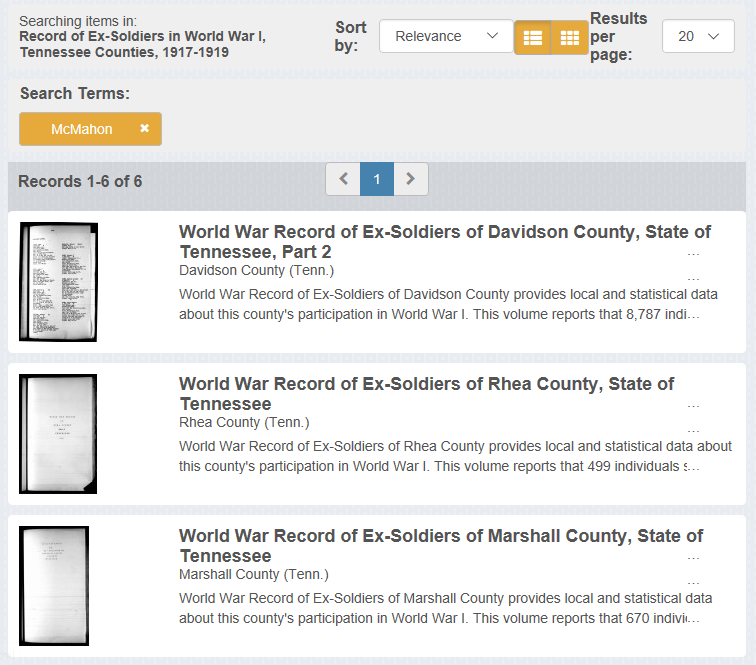

To search the records, enter the search term in the search box. Sometimes, I start by searching using just a surname. That way I can avoid missing entries because of spelling errors, or find other family members.

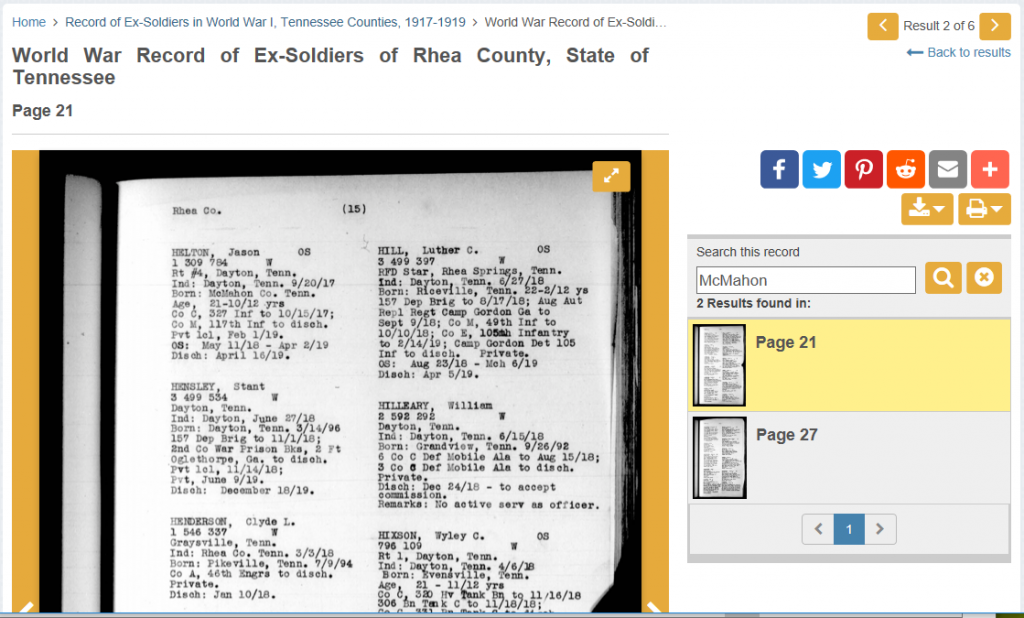

The results will have a list of the counties that have the results. Clicking on one will bring to the results for the whole county.

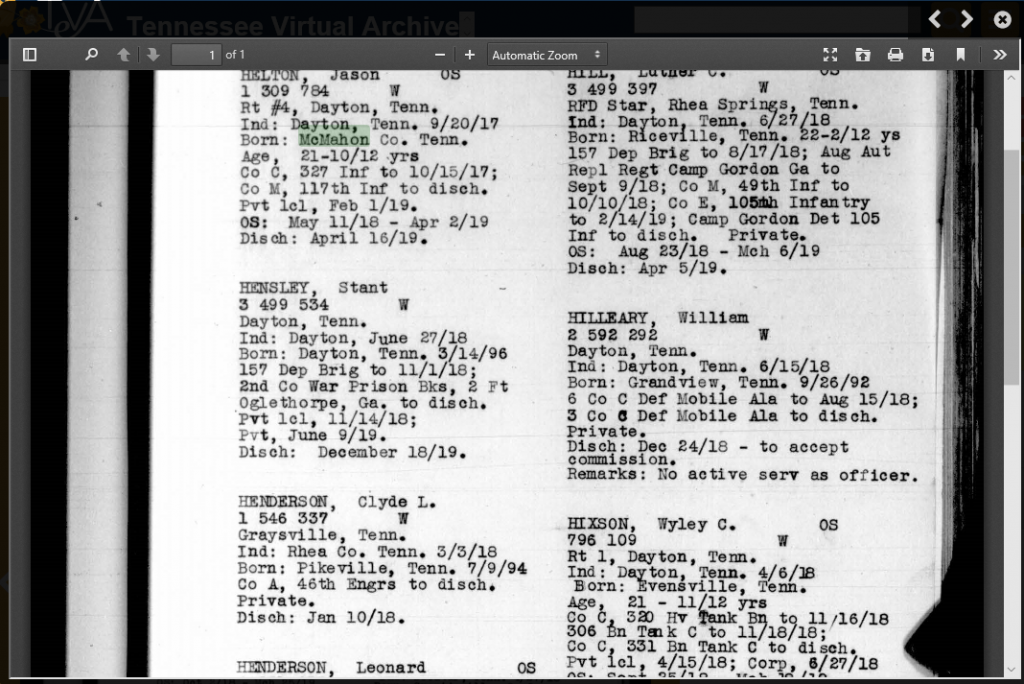

Use the arrows in the upper right corner of the pdf page that is displayed so that you can expand the view. In the expanded view, you will see the search term highlighted and you can download the page. From this view, you can use the arrows to move forward to the next result.

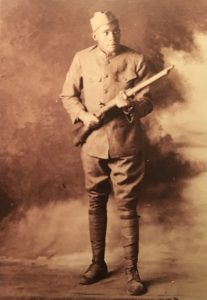

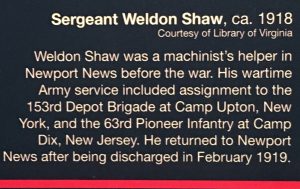

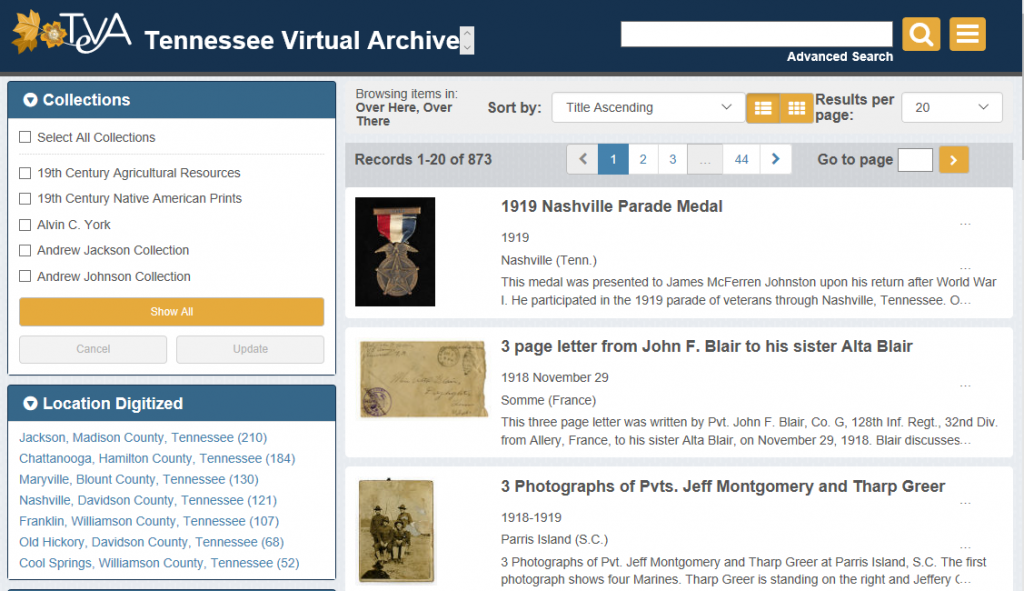

The Tennessee State Library & Archives launched an exciting project for the WWI Centennial Project called “Over Here, Over There: Tennesseans in the First World War”. Archivists digitally copied and advised individuals on how to preserve their World War I era manuscripts, artifacts, and photographs. The digitized copies of the items then become part of a virtual exhibit commemorating the centenary of the war and its impact on Tennessee.

When searching the database, it is incredibly helpful to know in which county your ancestor lived. Another idea would be to check out the lists that were created by county that are here. Scroll down to the alphabetic listing of counties.

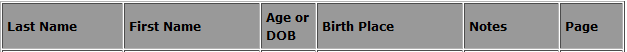

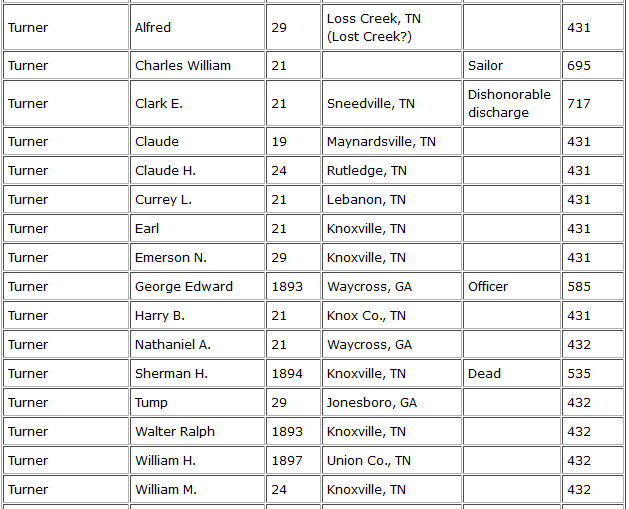

In this example, we are searching Knox County for the surname Turner.

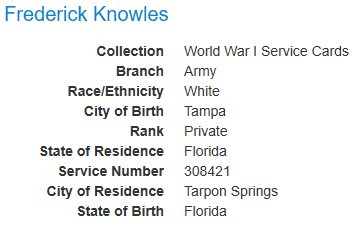

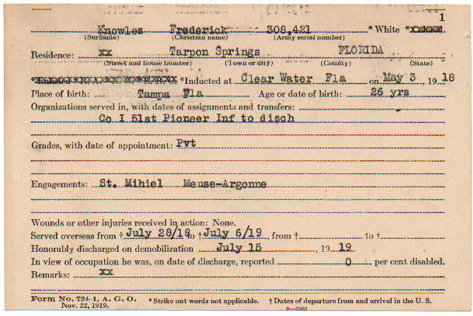

Using the page number listed in the column on the right will help in navigating the correct page from the search results. Using the Age or Date of Birth column can help narrow down to the correct ancestor when multiple soldiers have similar names.

You can learn more about the collection here.

You can browse the items or search this outstanding collection here.

While you are researching your Tennessee service member, consider checking Tennessee World War I Veterans’ Questionnaires. Although these Questionnaires are not digitized, they are indexed by the service member’s name. The county may or may not be listed. Although the 4,453 questionnaires that were collected represent less than 5% of the approximately 100,000 Tennesseans who served in World War I, the service member you are researching might be one of them!

If you find a survey from your ancestor, follow the directions here to order a copy of it.