The U.S. Military Records That Never Burned

No, NOT all the WWI and WWII military records for your ancestor were burned!

We often hear the misinformation and read many posts on Facebook claiming that all the military records burned. This post will help shed light on just a few of the records about your ancestor’s service that are still available.

We have already blogged about the Official Military Personnel Files OMPFs beginning here, and hope you had a chance to read about them. From that post you will have learned that Navy and Marine Corps personnel files from WWI and WWII were not burned in the NPRC fire.

It is important to know there were original records that were never in the OMPFs, and so, they were NEVER BURNED. These records were part of the paperwork generated by military organizations, and were kept separately from the individual personnel records. The individual personnel records were actually constructed by using these original records.

This blog post covers some great examples of records that could help you understand your ancestor’s military experience: Rosters/Musters and Morning Reports. For military ancestors who died while in service, there are WWI Death Files and WWII Individual Death Personnel Files (IDPF).

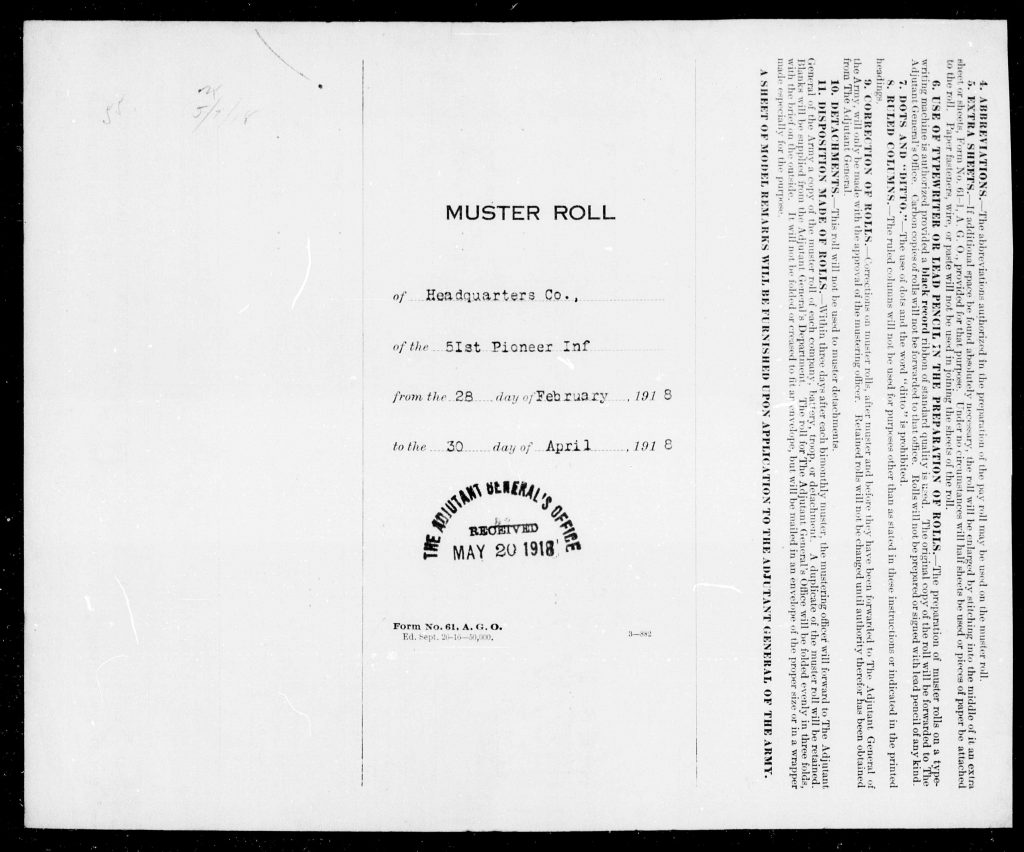

Muster Rolls and Rosters

These records contain information about service members who were in an organization, so you can place your ancestor with an organization at a specific time. These are lists of the members of an organization during a specific time period (or at a specified time such as the last day of the month). They shows who was sick in hospital, who was “lost” to the organization by transfer, and to where they were transferred, who was “gained” by the organization through transfer, and who was attached. By piecing these together, a service member can be tracked.

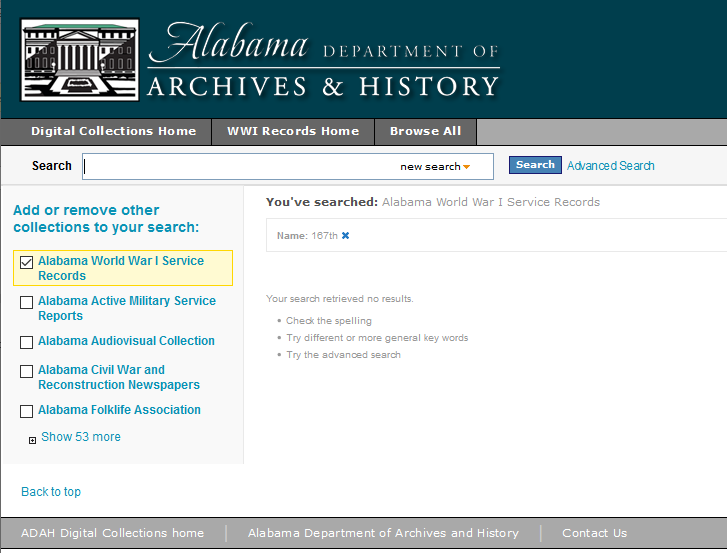

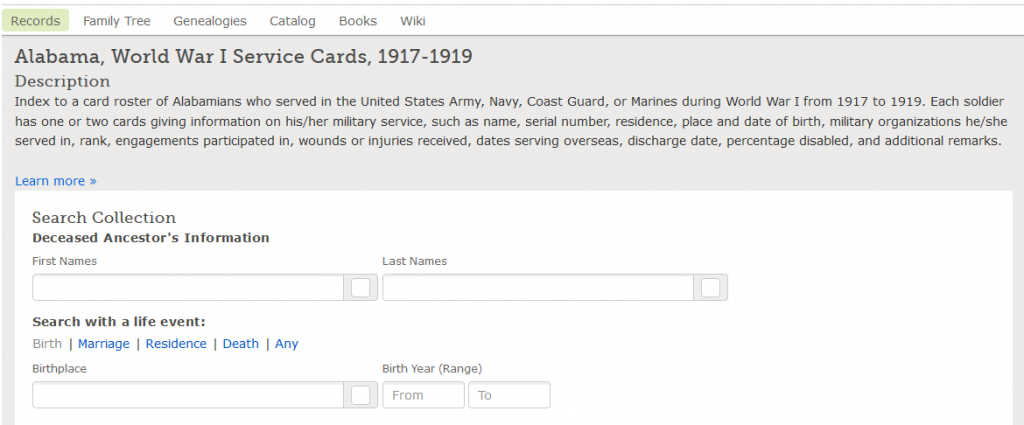

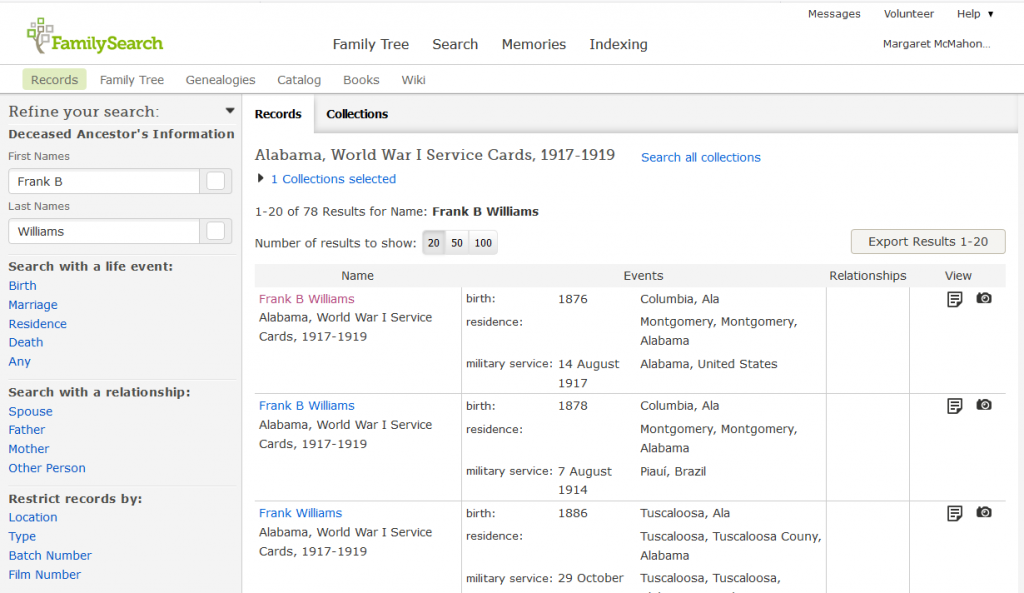

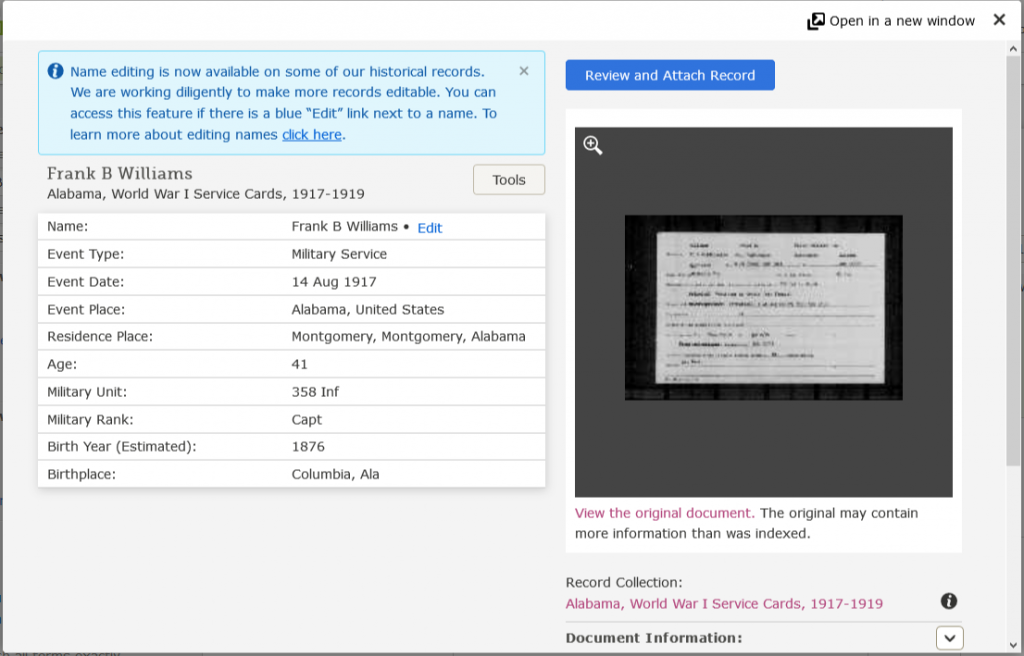

Browsable images of WWI muster rolls and rosters are available online at the FamilySearch website. You need to know the military organization for the service member because these are not searchable. United States, World War I, military muster rolls and rosters, 1916-1939 (The filmstrips are available at the National Personnel Record Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, MO.)

Morning Reports

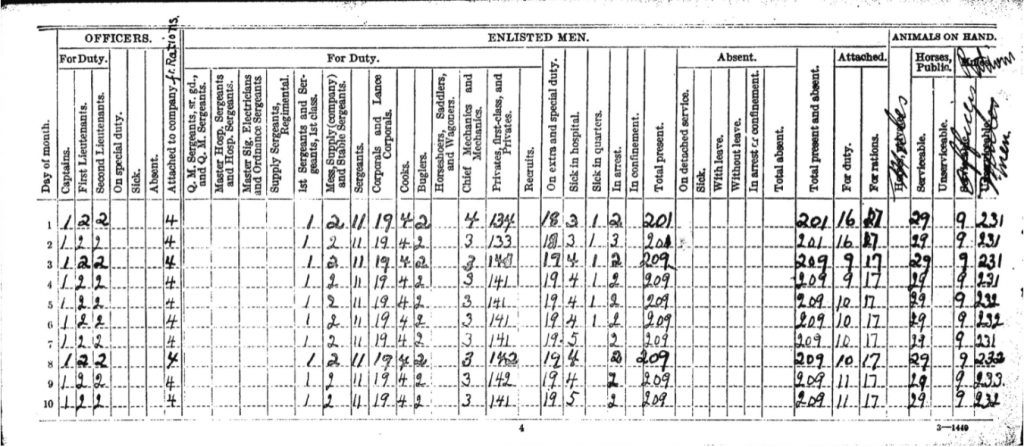

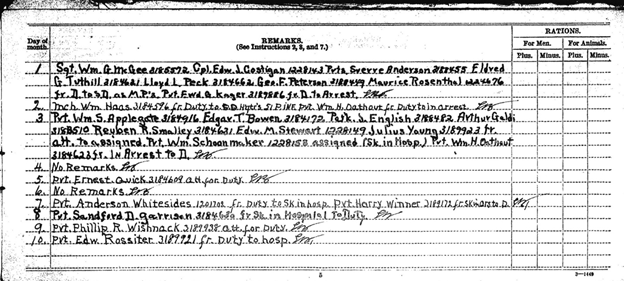

These reports cover the day-by-day details of an Army organization, giving a brief summary of the status of the men and animals in the organization.

The front of the morning reports contain columns that record the counts of officers, enlisted men and animals. On the back, brief notations were made naming the soldiers who transferred in, transferred out, transferred to a hospital or were sick. Notes were made of soldiers who were loaned out to other organizations, who were promoted, where and how far they traveled, courts martial, and disciplinary actions.

Like any other diary, this will give context to your military ancestor’s service even when his name is not mentioned.

These records are available at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC). The U.S. Navy has Ship’s Logs, which rarely mention individuals. Learn more about Ship’s Logs here.

WWI Death Files / WWII Individual Death Personnel Files (IDPF)

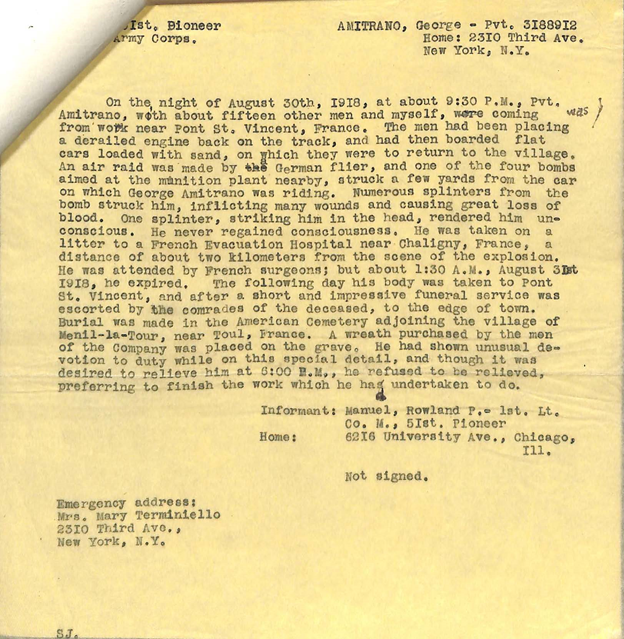

For service members who died while in service, a death file will exist. In WWI, these are Death Files; in WWII they were called Individual Death Personnel Files (IDPF). These files are truly individual, as the contents will vary for each case. Each should contain the circumstances of the service member’s death. If the ancestor died in combat, there will generally be a description of how he died, compiled from available witnesses.

For an ancestor who went overseas, the file will contain correspondence with the next-of-kin to establish whether to ship the service member’s remains back to the United States, or bury him in an overseas military cemetery. In the file for a WWI service member who was buried overseas, there may be information about a Gold Star trip sponsored by the government to allow mothers and wives to visit the grave of their fallen soldier in Europe. If the service member was originally classified as missing in action, the file may contain information about how the remains were identified.

Although these files exist for those who died during service stateside, typically these files contain less information that for those who died in combat.

These records can be requested from the NPRC, however, NARA is prioritizing the digitization of WWI files and making them online. Record Group 92, Series: Correspondence, Reports, Telegrams, Applications, and Other Papers Relating to Burials of Service Personnel, 1/1/1915 – 12/31/1939 are searchable here.

Burial Cards

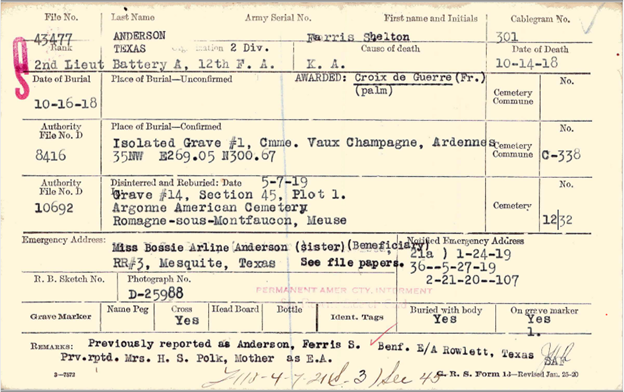

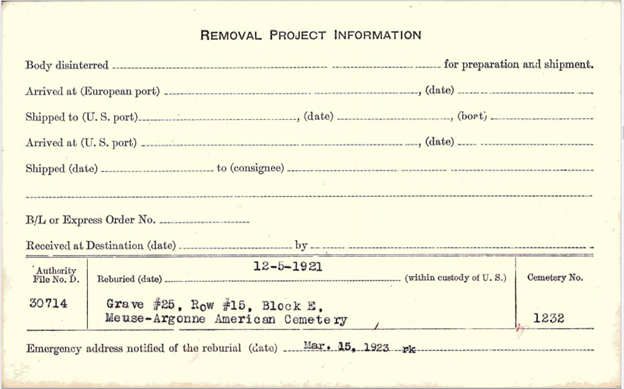

For service members who died while in service, a burial card will exist. The burial card contains information about where the service member was interred, and where the remains had been relocated. (To learn more, read the blog post Researching Soldiers Who Died During World War I.)

The family of the soldier below chose to have his remains stay in Europe, in the American Battle Monuments Commission Meuse-Argonne Cemetery. NARA Archivists have reported not yet finding where the photographs are stored that are referenced on the cards.

Record Group 92, Series: Card Register of Burials of Deceased American Soldiers, 1917 – 1922. The 104 sets of digitized cards can be browsed from here.

Know that only the personnel records for Army and Air Force service members were involved in the fire, and that even those ancestors still live in the unburned pages of the military records.