Tracking the Rev. Fr. Thomas Kennedy

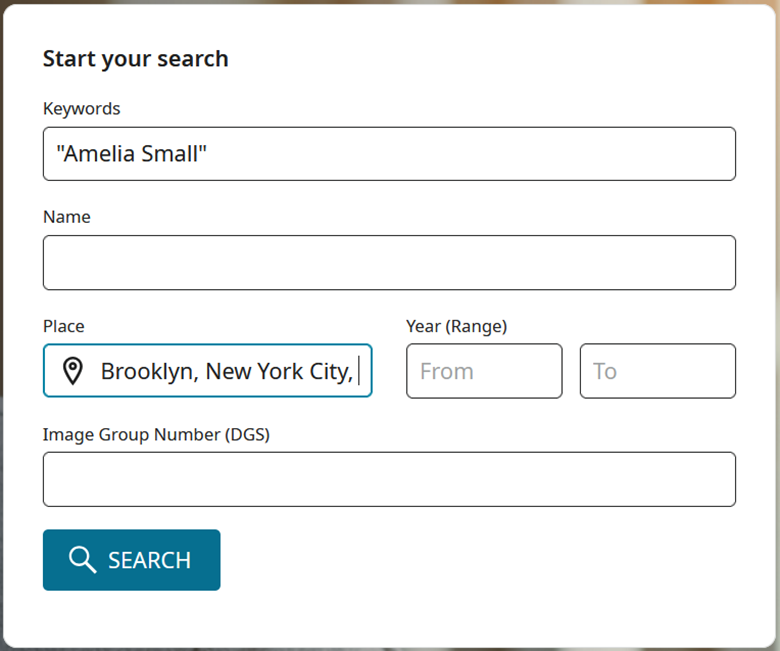

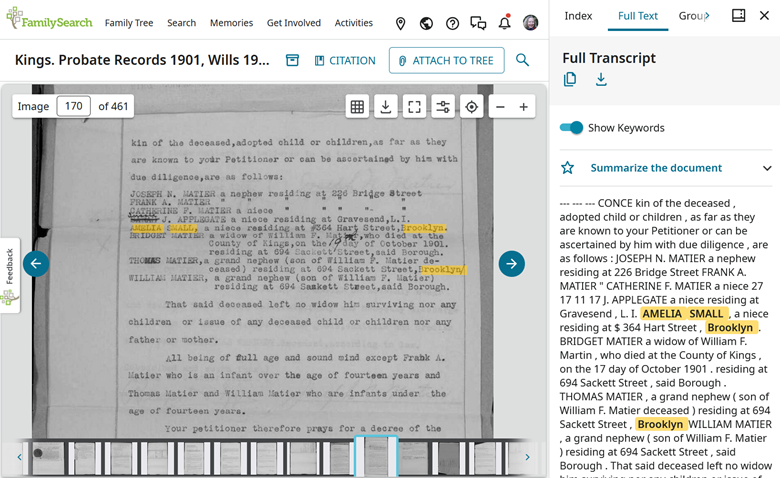

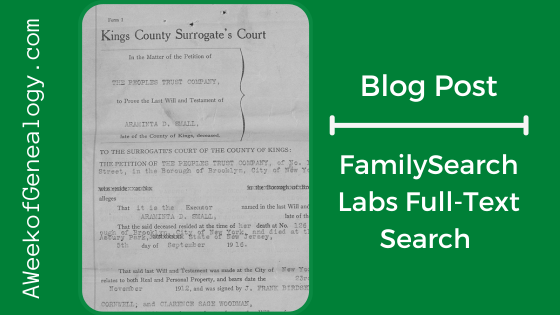

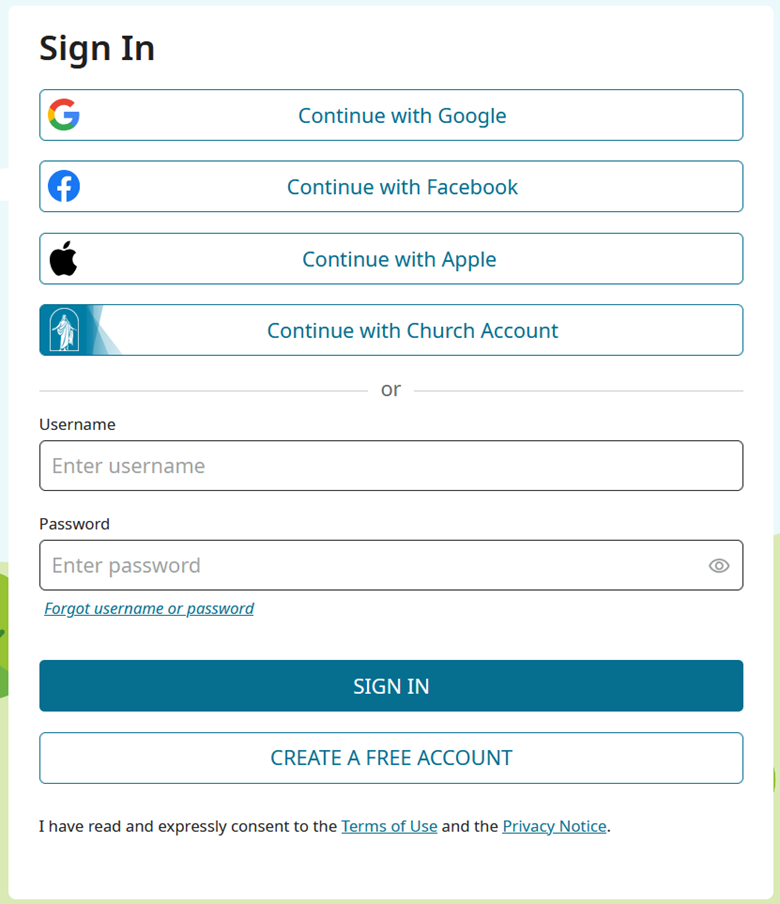

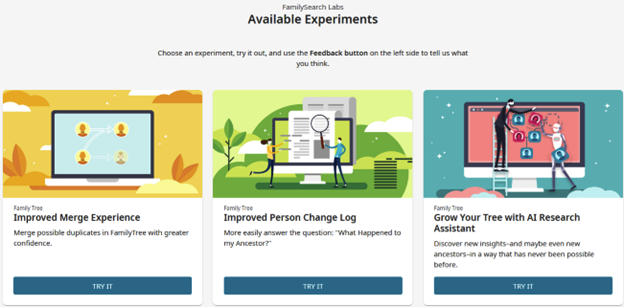

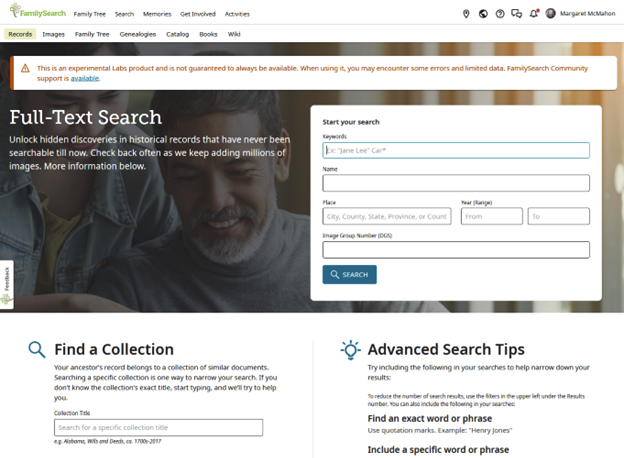

Previously I posted about getting up and running with FamilySearch Labs: Full-Text Search and how I learned about a new ancestor in Finding Amelia Small in FamilySearch Full-Text Search. Everyone is connected to relatives, no matter how isolated they appear to be. It may be that I located a lead to a collateral relative who might help to answer these questions about Amelia Matier Small’s mother:

1) Where was Mary Kennedy born?

2) Who were Mary Kennedy’s parents?

What I knew:

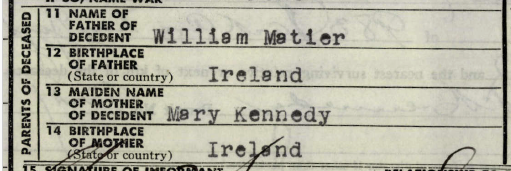

Amelia’s parents were William Matier and Mary Kennedy

How I knew those facts:

Amelia MATIER Small’s death certificate (New York City Municipal Archives D-Q-1946-0009408).

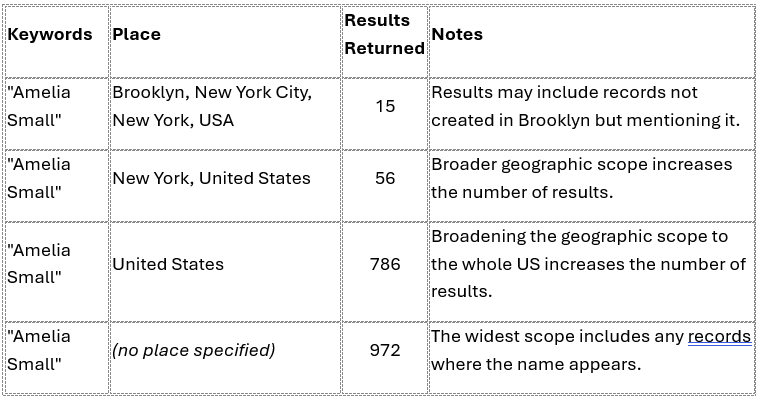

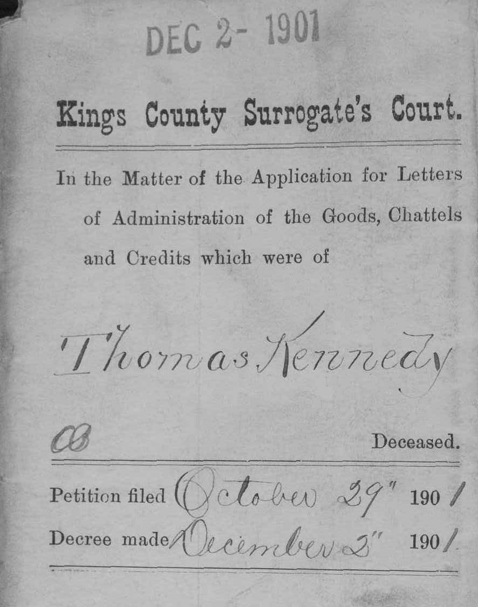

Amelia Small was referred to as Thomas Kennedy’s niece (from the Application for the Letters of Administration for Thomas Kennedy)

What I learned from this document:

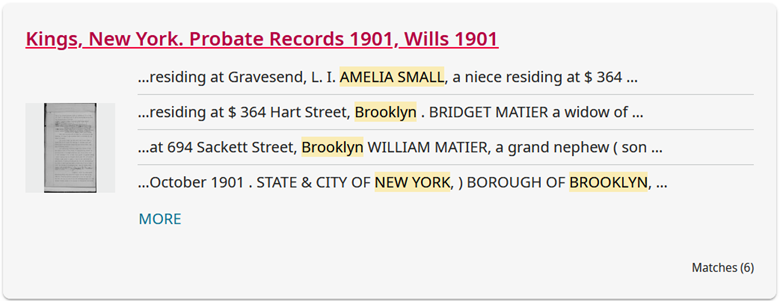

JOSEPH N. MATIER, a nephew residing at 226 Bridge Street

FRANK A. MATIER, a nephew

CATHERINE P. MATIER, a niece

CASSANDRA L. APPLEGATE, a niece residing at Gravesend, L.I.

AMELIA SMALL, a niece residing at #364 Hart Street, Brooklyn.

BRIDGET MATIER, a widow of William F. Matier, who died at the County of Kings, on the 24th day of October 1901, residing at 694 Sackett Street, said Borough.

THOMAS MATIER, a grand nephew (son of William F. Matier deceased) residing at 694 Sackett Street, Brooklyn.

WILLIAM MATIER, a grand nephew (son of William F. Matier) residing at 694 Sackett Street, said Borough.

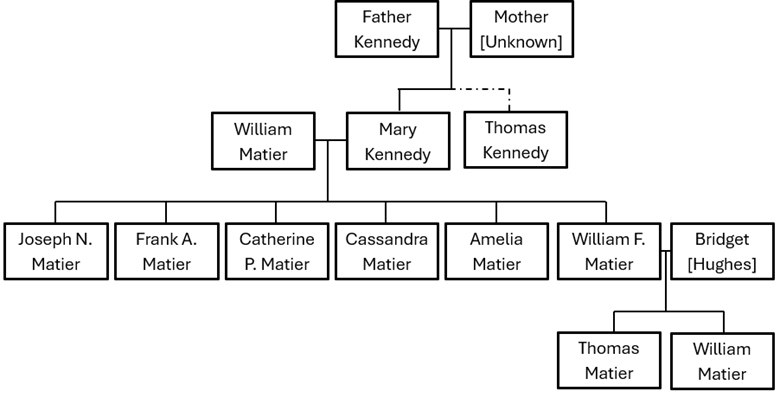

I sketched out a simple tree to combine data from the previous documents into my hypothesis:

Note: Other names and relationships have been omitted from this graphic. (Keeping an open mind, the possibility exists that Thomas Kennedy might be William Matier’s half-brother or adopted brother.)

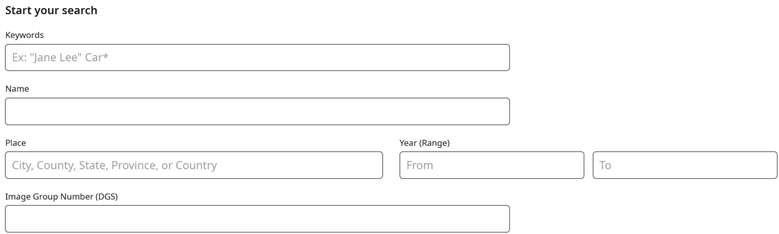

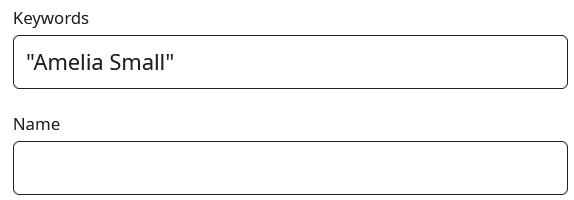

After reviewing what I knew, I cast a net to find US documents about Thomas Kennedy.

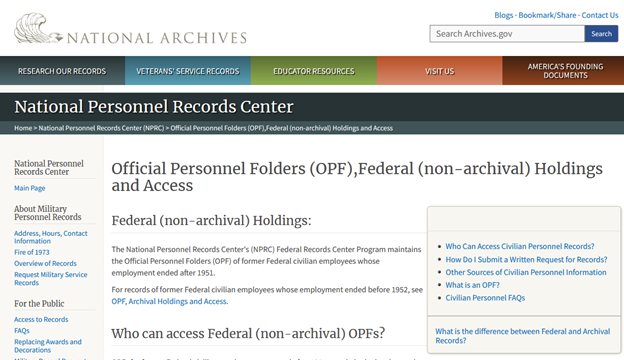

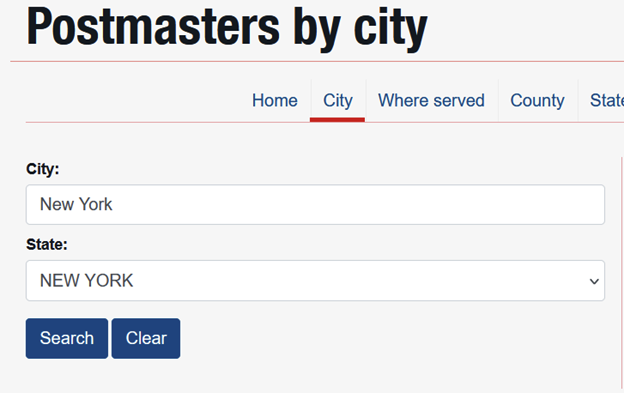

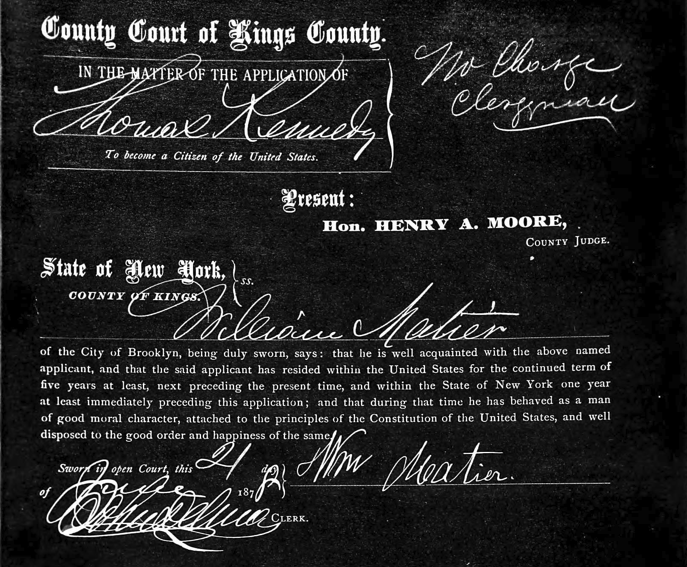

Using Full-Text Search for William Kennedy in Brooklyn, Kings, New York yielded several results, but it can be difficult to connect someone with a common name to a family. One result was the Application of Thomas Kennedy to become a Citizen of the United States that contained the signature of William Matier attesting to his residency and character. William Matier is the name of Mary Kennedy’s husband, so finding this combination of names might suggest that Thomas Kennedy’s brother-in-law was vouching for him. This document is dated 21 June 1882, and there was an interesting notation at the top: “No Charge Clergyman.”

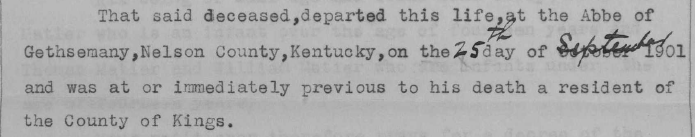

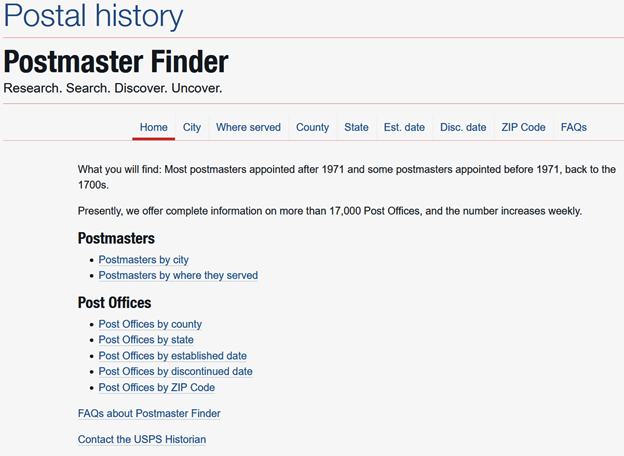

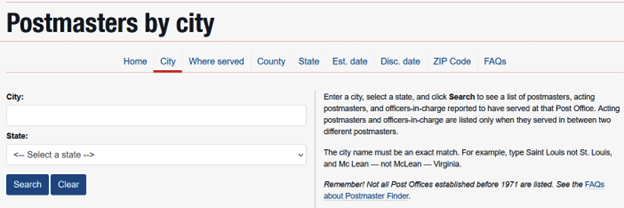

Since I had Thomas Kennedy’s place of death and date, I searched for him on Findagrave.com, but could not locate a record for him.

I turned to Ancestry.com to search for other documentation. Ancestry did suggest a Findagrave memorial. This one was for Rev. Thomas F. Kennedy, buried at the Abbey of Gethsemani Trappist Cemetery. The reason that my previous search did not work was that the first name had been listed as “Rev. Fr. Thomas” in the Findagrave memorial rather than “Thomas.” The name, death date and location of the tombstone matched what was known from the Application for Letters of Administration. From this it seems reasonable to conclude that Thomas F. Kennedy had been a priest. As it turns out, there are two memorials for this ancestor in the cemetery, with different pictures of the tombstone (Rev. Fr. Thomas Kennedy and T. Kennedy).

Photo courtesy of Robin Jordan

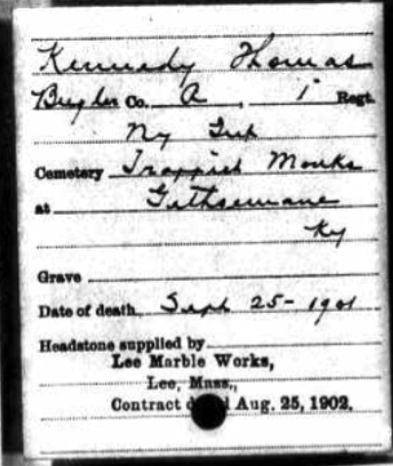

Another record that Ancestry.com offered in the search results was for a military tombstone for Thomas F. Kennedy in the U.S., Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, 1861-1904 database. This was an interesting development. The name, date and location of the burial matched what we knew about the Rev. Fr. Kennedy. We can now add that he had been a Bugler in Company A, 1st New York Infantry Regiment.

I followed Ancestry.com search results to entries in online obituary collection but none of them matched. (The Rootsweb Obituary Daily Times Index is now hosted on Ancestry.com.)

I did search the newspaper databases to which I had access for Thomas Kennedy in Brooklyn, New York, and in Kentucky, but there was no clear success. It could be my search terms, or the collections of newspapers. There was a mention of a Thomas Kennedy in Brooklyn being ordained at St. Bonaventure, so I kept track of that entry as a potential clue.

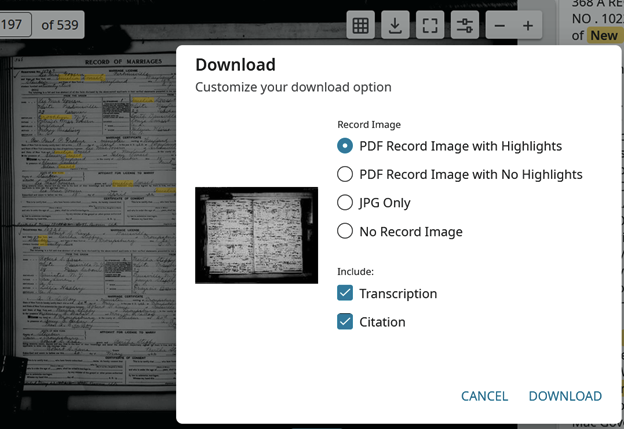

Of course I opened up a document and saved the images, citations and notes as I went through these searches. Of course it slows us down when we want to click through and follow each lead, but there is nothing more frustrating that wondering how or where we located a record. Stop, document and save!

I also reflected on how one document found through FamilySearch Lab’s Full-Text Search could launch a whole new avenue of research for me to follow.

The next thread to pull on is what can be found in Thomas Kennedy’s Civil War records. This will be covered in a future blog post.