Surname Study and AI Part 2: Collecting Census Data

In the Surname Study and AI Part 1 post, I described the reasons that motivated me to undertake a surname study in Rhode Island, US, and the approach I took. The use of AI tools to help with formatting, visualizing and analyzing data is a goal in this latest iteration of the project.

Both US Population and Rhode Island State Census data were used as a backbone for the study.

My next step was to use AI to capture the transcriptions of key record information from the censuses, and work to normalize it. For this first step, I decided to limit my search to census databases, for exact and similar spelling of the surname, using the exact location of Rhode Island, USA. Even though I collected the images of the census, I collected the data presented on the Record Page to populate the columns of the spreadsheet.

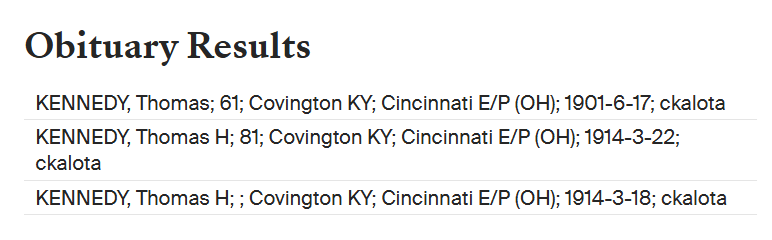

My search settings were:

Last name: Gilroy; Slider: Exact and similar

Lived in: Rhode Island, USA ; Slider: Exact

Focus: United States [this setting was not necessary because I searched for records specific to the United States and Rhode Island]

On the search results page, I used filters to narrow down to one census at a time so that I could collect the data.

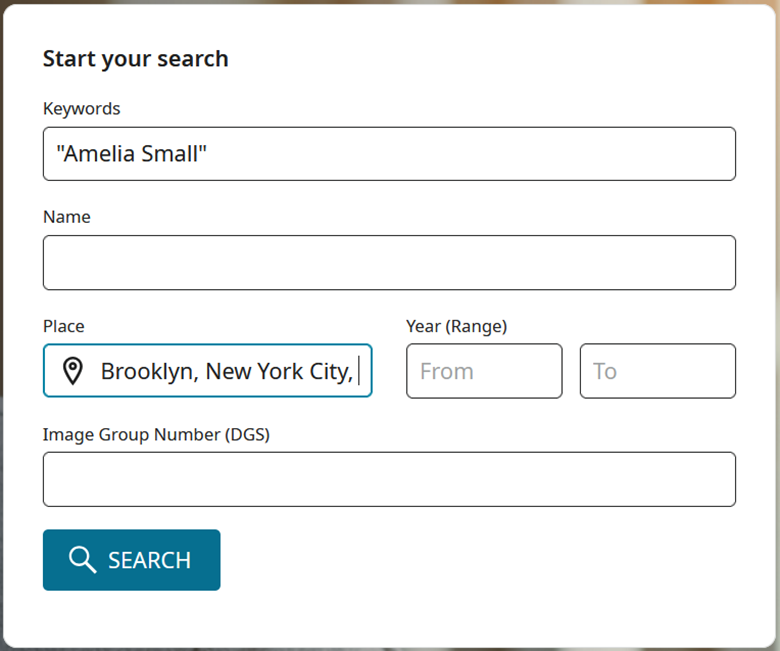

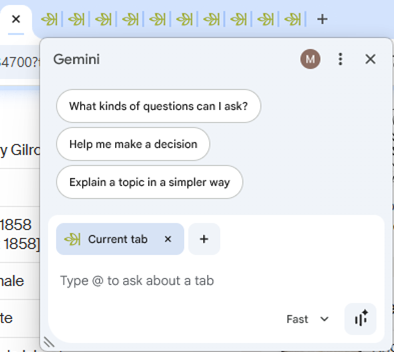

Thanks to a great idea I learned from Jon Smith of the North Carolina Genealogical Society, I decided to use Ancestry.com in a Chrome browser with Gemini AI enabled to capture the Record pages.

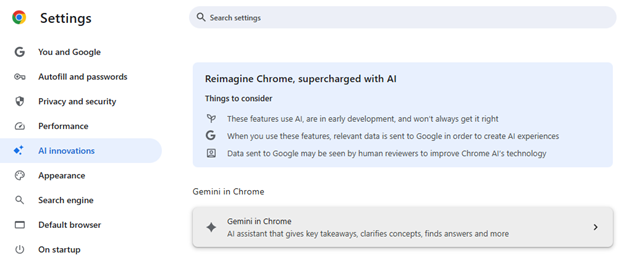

If you do not see Gemini on the top of Chrome:

First, be sure that you are logged into your Google account. You can do this by logging into your Gmail account in the browser.

Then, try this to enable Gemini in Chrome:

Click the three dots (More), and select Settings from the menu

In Settings, click AI innovations in the left menu, then select Gemini in Chrome.

To collect the data in the US Census, I signed into HeritageQuest in the Chrome browser. Always check your county library, as HeritageQuest may be free to access from home.

I searched for all the occurrences of the surname in Rhode Island, one census at a time for the 1850, 1870, 1880 and 1900 US Censuses. My plan was to collect one line of data for each name that appeared in the search results.

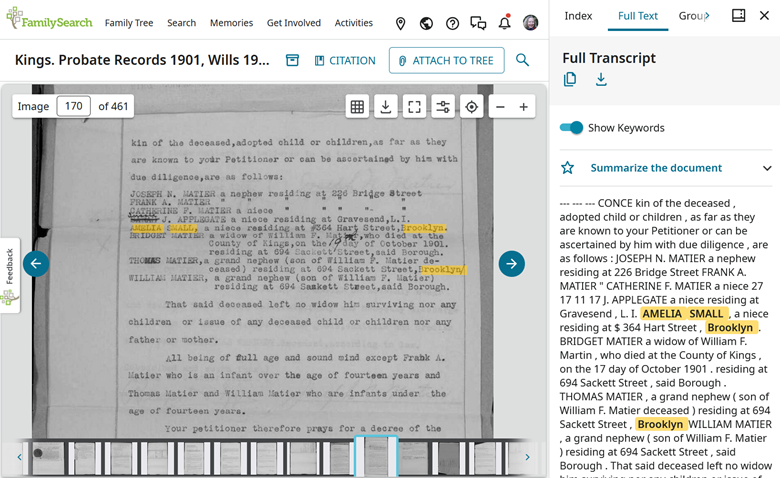

These are example results for the search for exact and similar surnames to Gilroy.

Example Search Results Page (courtesy HeritageQuest.com)

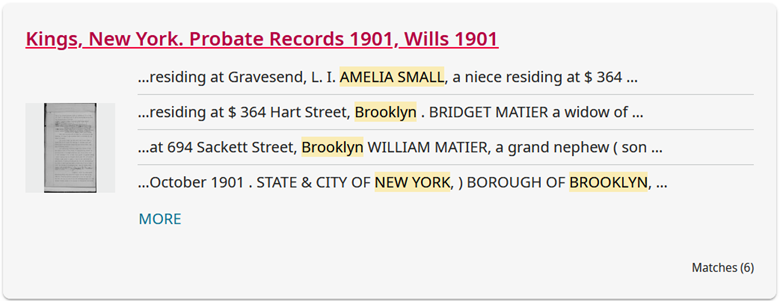

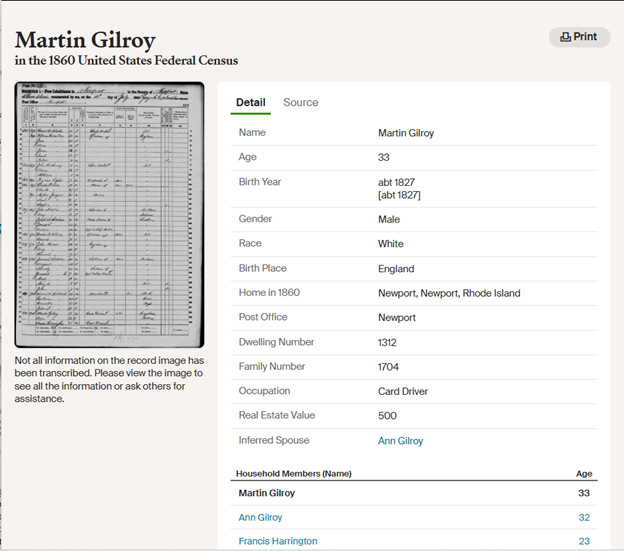

From the 1860 US Census Search Results Page, I right clicked on the View button to open each Record in a new tab.

Example Record Page (courtesy HeritageQuest.com)

Some of the issues and limitations that I found may be due to the fact that I use a free version of Gemini. I had to work on my prompt to have the data captured in a Comma Separated Values (csv) format, so that I could use the data from the transcription of the record in my Excel spreadsheet. I tried to have Gemini decide what to label the columns, but it worked out better when I told it the names of the columns in the prompt.

NOTE: Later on, Gemini and I decided to format the collected data in Markdown tables. This simplified the process, because the data could be pasted directly into the Excel worksheet.

In the interest of time, I used copied all the data from one Record page and asked ChatGPT to extract the data tags, using the prompt:

keep only the data tags such as Name, Age, etc and show them in a comma separated sentence on one line.

That provided me with column names which could then be used in the Gemini prompt. (This was done once for each census.) That way the line for each enumerated person in a worksheet would have the same data in the same columns.

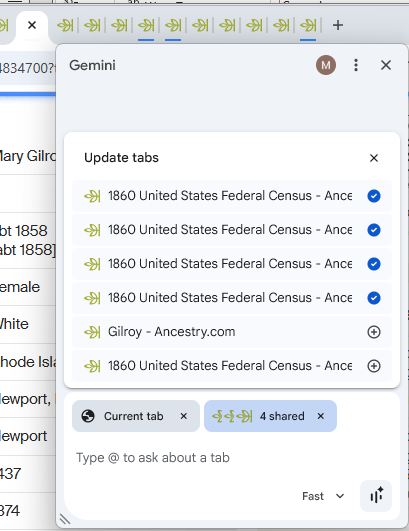

In my type of account (free), Gemini would only look at ten open tabs in the Chrome browser as input to a prompt, so I knew that I would have to collect the data in steps. Gemini wanted to jump right in and give me analysis based on the data in those tabs, and it took some coaxing through prompt refinement to get the data in a form to put into a spreadsheet.

I added tabs using the plus sign until I had selected the Current tab and 9 others to share with Gemini. (When you select more than 10 tabs a warning appears: “Only 10 tabs can be shared.”

Select Multiple Tabs as Input to the Gemini Prompt in Chrome Browser

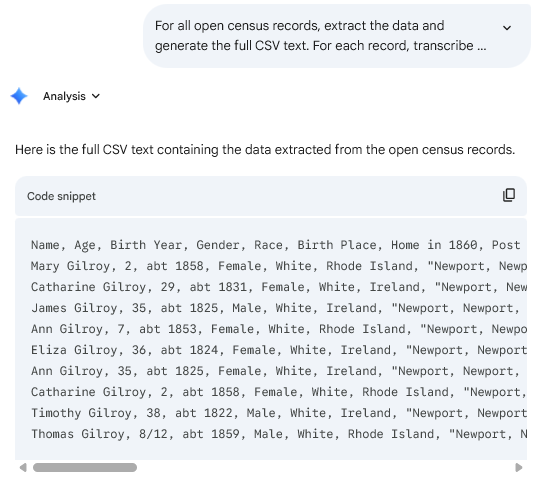

Prompts may need refinement, and in this case Gemini and I chatted back and forth to get the results that I wanted. Gemini warned me that it could not directly create or download an Excel (.xlsx) file for me, but that it could format the data into a standard CSV (Comma Separated Values) format.

For the 1860 US Census, this is a prompt that I used in Gemini in the Chrome browser. This was the result of refinement, and needed to be changed slightly for each census.

For all open census records, extract the data and generate the full CSV text. For each record, transcribe it into a new row of the CSV . Put the CSV text in a canvas so that I can copy it from the prompt. Structure the output so that each record (the main person detailed on the page) is a single row, and list all their household members’ names in a single column titled ‘Other Household Members (Names)’. **Only transcribe data explicitly visible in the current tab’s detail and household sections.**

Here are only the data tags, formatted as a single comma-separated line:

Name, Age, Birth Year, Gender, Race, Birth Place, Home in 1860, Post Office, Dwelling Number, Family Number, Occupation, Real Estate Value, Inferred Spouse, Household Members (Name)

**For any column field where data is not transcribed, insert a blank space to ensure all records have identical column structures.**

The response included this CSV text.

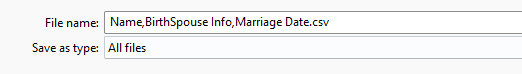

I used the copy icon at the top right to capture the CSV text, and pasted it into an open Notepad file. The Notepad file was saved as type “All files” and I created a file name ending with the extension “.csv” (CSV = comma separated values)

Then I opened the CSV file in Excel, and copied and pasted the lines into the Excel worksheet.

It seemed that when Gemini was used in the browser, it did not have a large memory, so I would have to reload the prompt during my next session. (Always save your prompts!) Sometimes Gemini wanted to use older data for the task I was giving, so I needed to modify the prompt to remind it to only work on the set of selected tabs.

Since this version of Gemini-enabled browser only allowed me to work on 10 tabs at a time, I stepped carefully through the results to be sure that each person with a name that was Gilroy or similar was included.

In an Excel spreadsheet, I pasted the data from the 1860 census in a worksheet, and labeled its tab “with the year and the type of census”1860 US Census.”

I repeated these steps for each US Population Census.

The Rhode Island state censuses are available on Ancestry.com, and I repeated the same process for each one.

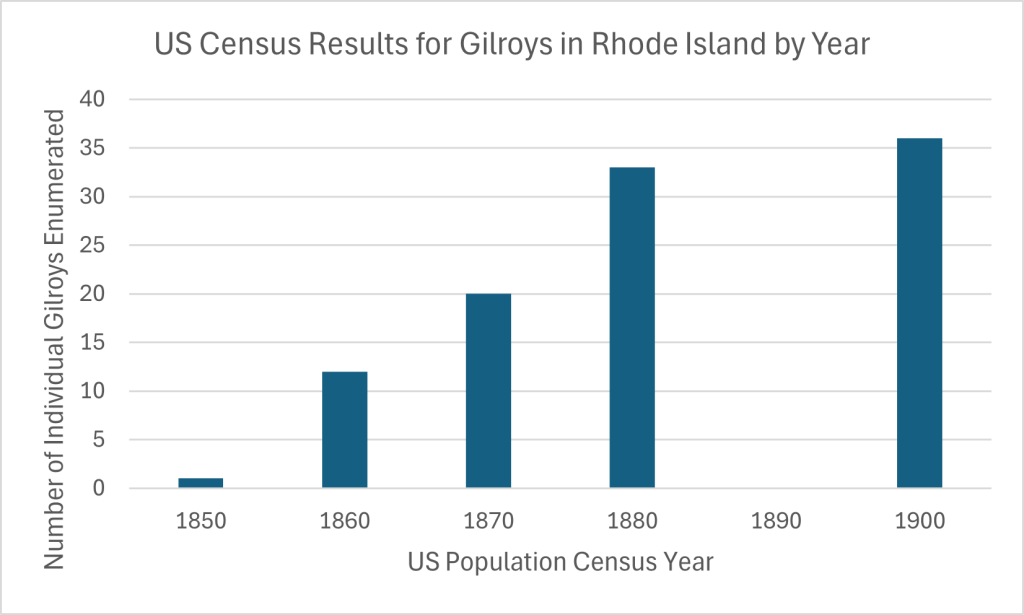

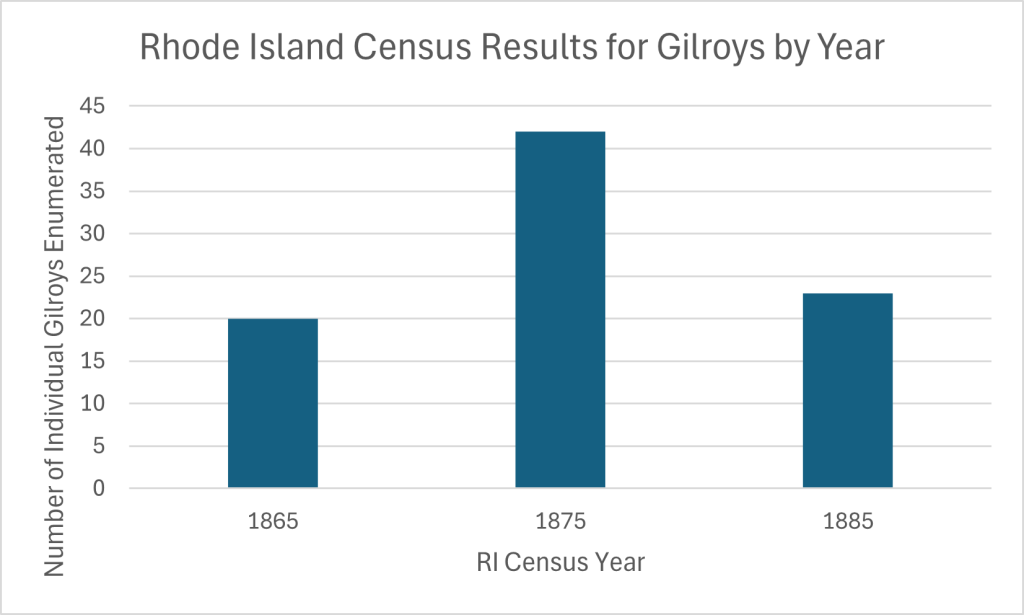

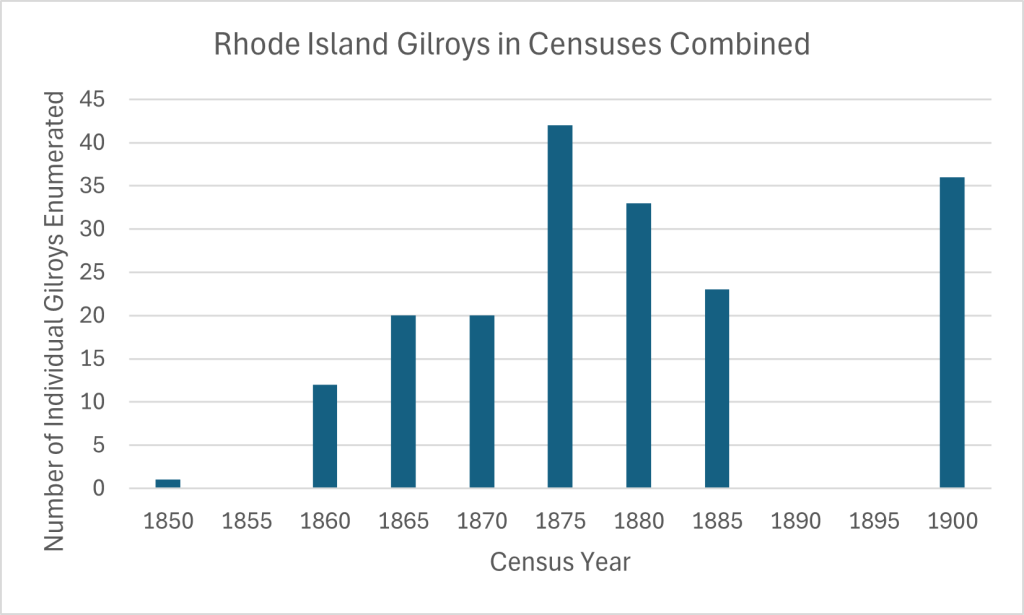

Engineers do enjoy visualizing data, so using Excel, I created a graph of the number of individuals with the exact surname Gilroy or a similar surname for each type of census. Then I combined the number of individuals from both types of censuses, for all available years. Note: the US Census for 1890 and the RI State Census are unavailable.

The story that I know from my hands-on analysis involves people with the Gilroy name arriving and departing Rhode Island through immigration or moving from or to another state in the US. The number of individuals with the same surname varied by marriage, birth and death. Women would either gain the surname through marriage, or lose it when enumerated using their husband’s surname.

Even though I did collect the citations from Ancestry.com, they are not sufficient for publication and I would have to do some more work to create any citations. There are limits to the approach I used. The enumerators may not have visited all the people who shared that surname, and that different transcription efforts may result in different spelling of the surname.

At the end of this step: I had an Excel spreadsheet, with a worksheet for each census. Each worksheet contained a line for each person who was enumerated in the census as having the exact surname Gilroy or a similar surname that was present in the online databases. Each column in a census worksheet has the same type of data, or was blank, for ease of analysis.

Next, I can use an AI tool to analyze the data in each census, and across censuses. My goal is to identify family groups as well as individuals and track their changes through the years of interest.